37: Brett Baer

“And the stunt coordinator says, ‘men, you’ll be jumping from THAT tower.’ And I thought, I can’t go through with this.”

From the Episode

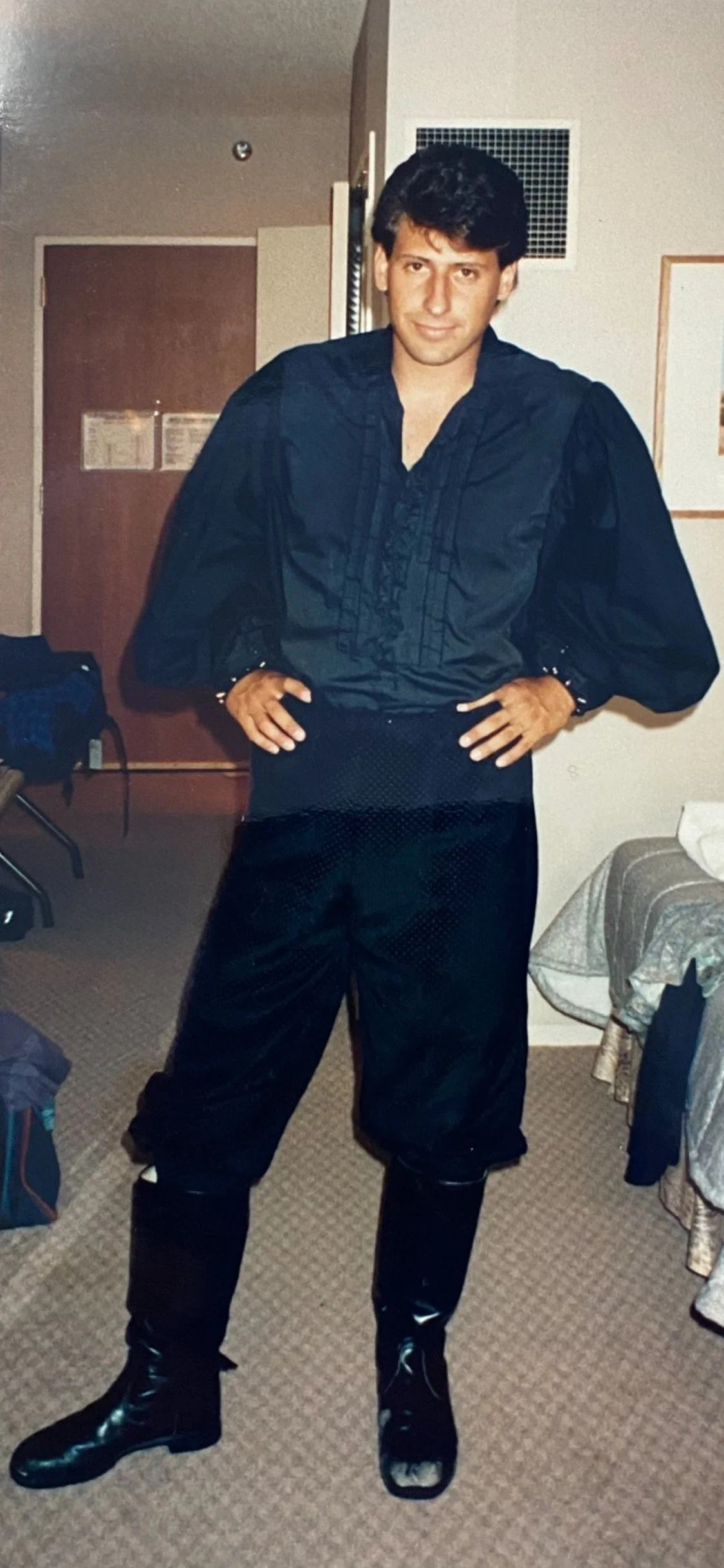

About Brett

Brett Baer is an Emmy Award-winning producer and writer that has worked on shows like New Girl, 30 Rock, United States of Tara, Joey, and more.

Growing up in Deerfield, IL, Brett was so captivated by television, he converted his parents’ basement into the Hollywood of the Midwest, deconstructing cardboard boxes to recreate the swamp from MASH, the studio set from Letterman, and other classics of the day… and, while other kids played with legos, he bribed his sister and neighbors with twizzlers to be his on-air talent.

Fast forward to the early 90s, when Brett decided that the entertainment industry was finally ready, moving to LA to attend the University of South California’s School of Cinema-Television. After dazzling his classmates at the Groundlings Sunday company, he joined ACME Comedy Theatre, the legendary sketch group where he would meet his writing partner Dave Finkel.

Moving on to take the world of animation by storm, Brett wrote for the Animaniacs and Pinky and the Brain, earning him a Daytime Emmy nomination for some of the wittiest dialogue this side of Family Guy.

Brett knew that he was destined for Primetime, however, and soon made his move to Norm, joining the ABC sitcom as a story editor. Stints on Just Shoot Me and Happy Family followed and in 2007, finally vindicated, Brett won the Outstanding Comedy Series Emmy for 30 Rock, which he co-executive produced. Not satisfied with just one award, he took home another Emmy for his work on the United States of Tara. Finally, that mere nomination for Pinky and the Brain was a scar healed.

Along with his partner Dave, Brett went on to create the hit series New Girl and, more recently, Bad Sisters, a binge-watchable show now streaming on Apple TV+.

Brett isn’t just a writer, mind you. An avid reader with a seemingly effortless understanding of world events, Brett enjoys a healthy discourse on the intricacies and nuances of geopolitical relationships, and offers a balanced view to those who seek it.

A fanatical White Sox fan, Brett has an iron grip on all team stats and trivia, and when it comes to playing, he prefers pickleball, crushing his opponents, likely while regaling them with the news of the day.

But if you think he’s a boring, middle-aged suburban dad with a proclivity for watching baseball from the living room lazy boy, just tell him you’re in a hurry to get to the other side of LA. With an intimate knowledge of every artery leading into and out of the city, Brett will proceed to transform into Mad Max and get you to your destination on time, even if you soil yourself in the process.

Books

-

Max Chopovsky: 0:02

This is Moral of the Story Interesting people telling their favorite short stories and then breaking them down to understand what makes them so good. I'm your host, max Dripofsky. Today's guest is Brett Baer, an Emmy Award-winning producer and writer that has worked on shows like New Girl, 30 Rock, united States of Terra, joey and more. Growing up in Deerfield, illinois, brett was so captivated by television he converted his parents' basement into the Hollywood of the Midwest, deconstructing cardboard boxes to recreate the swamp from mash, the studio set from Letterman and other classics of the day. And while other kids played with Legos, he bribed his sister and neighbors with Twizzlers to be his on-air talent. Fast forward to the early 90s when Brett decided that the entertainment industry was finally ready, moving to LA to attend the University of South California's School of Cinema Television. After dazzling his classmates at the Groundlings Sunday Company, he joined Acme Comedy Theatre, the legendary sketch group, where he would meet his writing partner, dave Finkel. Moving on to take the world of animation by storm, brett wrote for the Animaniacs and Pinky and the Brain, earning him a daytime Emmy nomination for some of the wittiest dialogue. This Side of Family Guy. Brett knew that he was destined for primetime, however, and soon made his move to Norm, joining the ABC sitcom as a story editor. Stints on Just Shoot Me and Happy Family followed and in 2007, finally vindicated, brett won the outstanding comedy series Emmy for 30 Rock, which he co-executive produced. Not satisfied with just one award, he took home another Emmy for his work on the United States of Terra. Finally, that mere nomination for Pinky and the Brain was a scar healed. Along with his partner, dave, brett went on to create the hit series New Girl and, more recently, bad Sisters, a binge watchable show now streaming on Apple TV+. Brett isn't just the writer, mind you. An avid reader with a seemingly effortless understanding of world events, brett enjoys a healthy discourse on the intricacies and nuances of geopolitical relationships and offers a balanced view to those who seek it. A fanatical White Sox fan, brett has an iron grip on all team stats and trivia, and when it comes to playing he prefers pickleball, crushing his opponents likely while regaling them with the news of the day. But if you think he's a boring middle-aged suburban dad with a proclivity for watching baseball from the living room, lazy boy, just tell him you're in a hurry to get to the other side of LA, with an intimate knowledge of every artery leading into and out of the city, brett will proceed to transform into Mad Max and get you to your destination on time, even if you soil yourself in the process. And so, a man of many talents, of contradictions embodied in aspirations achieved. Brett Bear, welcome to the show.

Brett Baer: 3:00

Oh my God, where did you come up with all of that? I mean, honestly, I know exactly where you got it because I can tell the writing is my partner, dave Finkel. He gave you some of that, I'm sure. Oh my God, that's insane.

Max Chopovsky: 3:12

I actually wrote the whole thing myself.

Brett Baer: 3:14

Did you really? Well, now I'm nervous. I mean, I can't live up to that. I wish I was a little drunk.

Max Chopovsky: 3:19

Well, here's the thing. You don't have to live up to any of it, you've already lived up to it all.

Brett Baer: 3:24

Oh, I guess that's true technically.

Max Chopovsky: 3:27

Here step ahead of me. So set the stage. Is there anything we should know about the story before we get into it?

Brett Baer: 3:38

Yeah, yeah, I'll give you a little background real quickly. You kind of mentioned I grew up in Deerfield, illinois, which is on the North Shore of Chicago, which I know, max, you know very well, but for those who don't, it's the area of the planet where John Hughes made all of his movies, right, breakfast Club, home Alone, risky Business was shot there, which I was actually in. I had one line in Risky Business, but that's a different story, and it's not, you know, admittedly, the toughest part of town. It's not the inner city, but the school I went to had some very rough kids in it, because there were a lot of my classmates who were the children of some very tough people who were connected to, let's just say, the Chicago Syndicate, you know. So every recess was a little bit like the Sopranos. I mean, it was like they were literally cracking yardsticks over each other's heads or comparing their breastknuckles with each other under the jungle gym. One kid, tragically his father, went missing and then was found in several dumpsters around the city, and you know, that was like. So, even though it was just like John Hughes World, it was like directed by Marty Scorsese, you know. I tell you all that to tell you that I was not like. I was not one of these tough, rough kids. I was a slight boy. I was not the most masculine kid and I was, you know, a bit of a pixie. I enjoyed dancing and dressing up in costumes and putting on shows in my basement and these tough kids would play games like and I don't know if you can say this, but I'll say it anyway called Smear the Queer, which I'm just reporting the facts. That was what the game was called, smear the Queer, and you can only guess who they wanted to smear. It was me, you know. So I got beat up a lot, I got made fun of a lot, I was bullied very hard and one day I just kind of lost it. I couldn't take it anymore and it led me to stand up for myself eventually and, I believe, also led me to one day leap three stories, almost killing myself in the process, live on CNN. Well, I mean, it wasn't, it wasn't live, it was, I almost wasn't live, but anyway, that's where sort of the setup for the story.

Max Chopovsky: 5:40

Oh my God. First of all, little did I know that some of the meanest gangsters of Chicago got their start on the main streets of Deerfield.

Brett Baer: 5:51

Yeah, Well, it's actually. There's a little incorporated area next to Deerfield called Riverwoods where it's very Sopranos like and you know, beautiful big homes, secluded and Floods a lot. Yeah, so they had a little facility and their father would answer and it would be like 5643 and you'd be like, instead of hello me, five, five, six, four, three. Okay, am I supposed to place a bet? Can Andy come out and play? You know that kind of thing. So yeah, you know, and the kids could be nice on occasion. I'm sure some of this is just my perception as a boy was beat up all the time, but it felt oddly rough and violent considering that it was, you know, it was dear filled.

Max Chopovsky: 6:32

Yeah, I love it. Into it. Tell me a story.

Brett Baer: 6:36

All right, I'll tell you a story. So everything I just told you. You know, like I said, one day, I just I couldn't take the bullying anymore and I decided I was going to stand up for myself. And I, I said to myself, you know what, no matter what happens, you're going to fight back. You are going to just take the hardest take you can, you're going to jump in there, you're going to fist, fly, kick, whatever you have to do. And sure enough, you know, I got picked on one day and I just I went for it and I lost badly. I got the shit beaten out of me, as I always did. But this time was different, because this time I refused to show any pain whatsoever. I was like I'm not going to let them see me hurt. And every time I got punched in the face I would just smile. And then, when the kid was done kicking the crap out of me, I got up, I brushed myself off and I just walked away and the pain in my face was so much less than the joy in my heart that this kid felt so impotent. It was so frustrated that he didn't hurt me. And I realized something that that might be my survival technique that could be my coping mechanism. So I taught myself to actually suppress the pain and I decided I would dictate these events myself and I started challenging these tough kids to do whatever the fuck they wanted to me. Let them punch me in the stomach as hard as they could, or kick me down the slide or throw me down the stairs, and I would just take it like a rag doll. And I actually trained myself to just absorb all this pain and a funny thing happened, which was they stopped picking on me. They were just more interested in like having fun throwing the office stuff and I could take it. And it hurt, believe me. It hurt Like I had the bruises and scars to prove it, but I wasn't getting beaten up. It was me in charge, or so I thought. So one day I used all these talents that I had developed, these sick talents, combined with some gymnastic skills I had and some acting comedy chops that I'm now using as a writer, and I actually became a really good physical comedian and over time I started earning money as a physical comic because I could do this stuff and people would hire me to fall down and go through walls and stuff, and I studied like the masters, like Buster Keaton, I studied religiously. Mo Howard of the Three Stooges was a great knockabout comedian. My favorite movie was Hooper starring Bert Reynolds, which was about the Hollywood's greatest stuntman, and that became my favorite film of all time and I watched it 300 times. So when I was 24 years old I got the opportunity to audition for the Universal Studios Western Stunt Show and I was like, oh my God, this is my calling, like this is what I think, this is my future. And I did great. I sailed through the audition. I was funny, it was fast, I could pretend to throw a punch, I could take a punch, I could fall down, etc. I could ride a horse. And on the last day they said to me OK, so tomorrow you're going to come back and we're going to do high falls into an airbag. I was like, huh, high falls into an airbag. That I'd never done before. I'd seen it. I mean it's a magnificent thing to watch these guys do this right, and we all see it in the movies and I always wanted to, but I'd never done it before and I was like, well, what the fuck do I do? I mean high falls into an airbag. I mean people die doing this stuff. I don't know if you, if you haven't seen the movie Hooper. There's this amazing high fall that the stunt performer named AJ Bakunas does, where he jumps 230 feet. It was a world record at the time off of a helicopter into an airbag, and it is a thing of beauty. Later, that same year 1978, aj tried to re-produce the record and he went through his airbag and died. So I mean, it's dangerous. And look, look, we were never going to be jumping anywhere close to that high. But I didn't know how high we were going to be jumping. I had no idea. So all night long I'm in a panic. I'm like what the fuck do I do? Like I can't do this, I shouldn't do this, I really shouldn't do this. But when I left for the audition that day, I looked across the street as I was getting my car and I saw it like a little two story roof and I said you know what, if it's that high, I can do it Anything higher, I'm just going to have to walk away. So I get to this stunt campus where we're doing these we're going to do these high fall auditions and I see the tower for the high falls and I go. Oh my God, it's exactly the same height. I said I could do this is fantastic. So they gather us up in. The stunt coordinator goes OK, ladies, ladies, you'll be jumping from that tower. And he points to the tower that I was talking about just a minute ago. And then he goes man, you'll be jumping from that tower up there and he points way over our heads and there's a tower that is so high over my head I didn't even see it and I'm like, oh my God, it was like three stories. I mean, it was a big deal. And I was like what do I do? I can't go through with this. But all of a sudden, that little kid on the playground. I looked around at all these professional stuntmen that I was going to be competing with here and I was like that. And they became the guys on the playground and I was like I have to, I have to come through Now. Look, the stuntmen were great. They were very friendly people. They were not the bullies, but in my mind I projected onto them this was the playground. Again, I was back on the playground. I had to go through with it. So they gave us some auditions I'm sorry, rehearsals for the audition, I should say, before we actually had to do our audition to do the high fall. When it was my turn, I didn't know what I was doing. I mean, there's a whole way of doing this, so you don't get hurt. I didn't know, I just knew what I'd seen in movies. And I had to climb up this little rickety ladder. That was like swaying and I don't know if I mentioned this, but I'm afraid of heights. So, yeah, that into the equation. And I keep climbing, and I keep climbing and I'm like where is the top of this thing? What am I doing? And I get on this little tiny platform that's about two feet wide by four feet long. It's a trapeze artist platform that you like, you see in the circus, you know those little platforms, that's what I'm standing on right, and I'm like, well, here goes nothing. And I do the fall. Boom, I hit the bag in a flip and it goes well, well enough, like I survived. And I was like you know what? That wasn't so bad. And I gotta say it doesn't feel good to land on an airbag. It's not like jumping into a marshmallow. It hurts, you know. It's like smacking a water balloon with the back of your hand, you know, but I did it. I got two more practice runs and I was feeling like you know what, good enough, like there were some people who were really talented. I was like I didn't even think I could do it. I did it Three stories into the bag. So now it's comes time for the actual audition. They've got us all going, one at a time, boom, boom, boom. And all of a sudden I look over and a CNN camera crew has shown up to I don't know why, but they're tape, they're gonna videotape this audition. Like it's a human interest story. It's like don't you have a Persian Gulf War to cover? Or something like that. So when it's my turn to go and they call my number, I start walking over to that little ladder I told you about and all of a sudden the CNN cameraman some big, dumb guy with a camera on his shoulder he starts climbing up the ladder in front of me and I'm like what the fuck is he doing? Anyway, I'm like, well, this is my audition, I don't have it. Nobody's saying you know, hey, don't go up there, dude. So now the two of us are on the ladder and it's swinging and I'm like what was scary before is now ultra scary. We get up on this tiny little platform I told you about. He's standing behind me shooting over my shoulder as I'm gonna do my fall and I'm like this I really don't need. I've only done this three times in my life and it's all been in the last two hours. So this stunt coordinator who was counting people down one, two, three, one, two, three he decides all of a sudden, now he's on camera, stunty McGee needs to be funny. So Stunty McGee starts doing like a like some stupid Western improv with me and I'm like, oh fuck. So I start improv-ing back with him because we're on camera, got it, it's my audition, I gotta do it. And he does one of those dumb jokes where he kind of goes like he goes you wanna see my quick draw, and then he doesn't move and he goes there, you see it. And I'm like that is the dumbest joke. And then all of a sudden he goes bang and I'm like, oh, that's my cue. Now I'm like I start going, like I got shot. I kind of grab my chest and I go back and I bump into the camera guy and I'm like, oh right, I forgot he's up. Oh, and at that moment I'm already going forward. All of my mechanics are off, I'm totally jacked up and I'm going, but I'm like falling and I can remember that feeling of like, oh, this isn't good. And I over-rotated so that my feet hit the bag first, which, if you can imagine, pushing down on one side of a balloon, the other side of the balloon comes up right. So my feet hit the bag first. The bag comes up from behind me and smacks me in the back of the head like a Mack truck hitting me. I'm telling you it was the worst pain I've ever felt. It hurt hard and I can hear everybody go. Oh, you know. And then I don't remember much because the whole world was spinning, everything was ringing, people were climbing onto the bag to pull me off and all of a sudden Stunty McGee's in my face making sure that I'm alive, that I'm okay, and the one thing I can remember from this moment is from the look in his eye. I was not getting this job. And the next thing I know the woman reporter from CNN is like got a microphone in my face and I'm probably speaking nonsense and gibberish. I have no idea what's coming out of me. So somewhere, probably in Atlanta, there's a tape of me making a complete ass out of myself. But I didn't die, and that is a victory in itself.

Max Chopovsky: 16:15

What a story. Okay, I have so many questions. You answered the first, which is you don't have the tape. I think that it's worthwhile tracking it down, because that has to be incredible.

Brett Baer: 16:31

I think I'm too afraid to look at it. But yeah, you're right, I should call somebody and say hey, I just wondered, do you have this piece together? But I mean, it was not pretty, I did not look good and I got hurt bad. I think I was concussed, you know.

Max Chopovsky: 16:47

Yeah, so did you end up getting it checked out? Or was this back in the day when, like, you're fine, just walk it off?

Brett Baer: 16:52

No, it was. You're fine, just walk it off. I swallowed the pain and I swear on my life. 45 minutes later I was doing another stunt for the audition where we had to do one of those I think they call it like swing for life, which is kind of like one of those rip line kind of things and you sweat, you know you come down a rip line, but then there's a release on it and then you drop into a bag. That wasn't as high, but I will tell you. The funny kicker to that story is, while we were doing that it wasn't me, but while we were doing that the airbag would inflate. The airbag would inflate, but in the middle of doing it we had an earthquake in California that day which knocked out the electricity and knocked out the generator on the airbag, and so, as they were about to do a stunt, the airbag started deflating and a guy almost was like mid-stunt when that happened. So again, like you know, I have such respect for these people. I really love stunt people. I've had the opportunity to work with a lot of them in my career and I really appreciate them and they do everything they can to protect the safety of the people they're working with, especially the great ones. My next neighbor is a stuntman who doubled Billy D Williams as Lando Calrissian, and he's a great guy. I love these people, I really do, and you recognize that there is no full proof, you know, safety net for them and something is always possible and they take that risk which you know I kind of admire, but it is a sickness.

Max Chopovsky: 18:28

That is crazy. What acting do you do when you're falling off a three-story tower?

Brett Baer: 18:36

Well, I'll tell you something. You know some of these guys are so good and so in control of their bodies that they can do different things in mid-air as they're falling that make it look like, you know, they're scrambling to try and save themselves. Or you know, there's different kinds of falls too. Like you know, doing a flip head over tail is one thing, but there's something that's actually harder that these guys do, where they'll fall straight down face first and then they're capable of turning their bodies in mid-air so they land on their backs without flipping, like a somersault, so they're just kind of rotating, and that is like the muscle control that it takes to be able to do that in mid-air. But these guys can do it. A lot of them were professional high divers who had then transferred over to like doing stunt work and instead of landing in water they were landing. You know I didn't want to even get on the high dive growing up at my local pool, but these guys are like doing flips and I mean some of them were doing like double flips and kips and turns and this and that, and it was very impressive but-.

Max Chopovsky: 19:35

I mean when you're standing and looking at the high dive at your local pool, it seems completely manageable. And then you get up on it and you're like, oh my God, like the perspective. Same distance, but the perspective is outrageously different. And I can just imagine looking at like a two, three story building, you're like that's fine. And then you get up and you're like, oh my God, I'm about to die.

Brett Baer: 20:01

I actually was going to tell you this for the proper perspective to understand what you're doing, you can stand up and put like a throw pillow, like a couch throw pillow, down on the floor at your feet or like a large coffee table book. That was the perspective I had. Now take a deck of cards and put it in the middle of that coffee table book. That's the red target that you're supposed to hit, in the center of the bag. So you don't, you know, go off the side or get bounced, and so when you're standing there looking down at a deck of cards at your feet, that's the feeling you have and I mean I can't believe I did it. But I think that those kids like drilled into me this desire not to give in and seem or feel weak. Now I will say it took me a lot of time, a lot of growing up, a lot of therapy to get to a point where it was like why are you so willing to abuse and hurt yourself to be accepted by other people? And getting to a point of going like, oh, I don't need to break my elbow or have a cracked vertebrae apparently I have I can be me Like it was okay to be that delightful little pixie but I was terrified into becoming this thing. That hurt me in many ways but it protected me and as I got older I was kind of able to sort of disentangle that infrastructure of protection from around me and kind of go like it's okay that I'm not you know, I'm not some big, tough, macho knuckle breaker, that's just not me.

Max Chopovsky: 21:44

Yeah, it almost seems like it was twofold. It was having a sense of control, taking back the control from the bullies on the playground, and also not being a threat to them by allowing them to do whatever it is they wanted to do, but on your terms, and so that was. It almost seemed like a coping mechanism. But what's crazy is when you're standing on that tower, you have to give up all control.

Brett Baer: 22:12

Yes, that is absolutely true. It's so crazy. It's really this very strange paradox, isn't it? Cause it's about like believing that you have control and yet you are genuinely not in control. And I think, ultimately, that's the takeaway or the lesson, which is that, or the moral of the story, that all of us probably find these coping mechanisms that, in the long run, are more perhaps I don't want to say damaging, but are not productive ultimately, and that there's a healthier way of taking one's journey in life that probably requires in a tremendous amount of inner confidence and strength that most of us, as young people, when these things get formed, don't have. We all grow up just trying to get by, and it goes in many different ways. I mean, some people become, for example, overstudious and they become dedicated to the A plus in a way that at 30 or 40, a lifetime of that starts to take a toll and they go, hey, maybe I need to enjoy my life a little bit more. What have I become? Because I'm kind of this automaton, so that's another version of it. Obviously, the harder things like drugs or alcohol, those are other coping mechanisms that probably feel like they're working in a moment and then one day they're not. So this was definitely something that I realized. It made me some money. I will say, dave and I, one of the first things we did that I don't think you mentioned was the Saturday morning TV show where we did silent knockabout comedy and throwing each other downstairs and through walls. That was the first professional, real professional gig I had, prior to the sitcom work that I did, but at what cost? Because there are times when I wonder am I going to have mental problems from all the pratfalls I did and the concussions I gave myself?

Max Chopovsky: 24:14

Did you end up doing any more stunt work after that, or was that the end of your stuntman career?

Brett Baer: 24:20

No, it wasn't the end. That was probably in the early 90s and Dave and I did our TV show, I think in 1997. I had been in sketch comedy and when I met David Ackme one of the things that drew us to each other was our love of physical comedy. One of the first bits he and I ever did together was a bit called Crazy Monkeys, where I don't know if you remember this, but there was a guy named Bobby Barracini who had a monkey act. He had a Norengatang act that used to always be on the Tonight Show. He performed in Vegas. So I played Bobby Barracini and Dave played all the monkeys and Bobby Barracini allegedly had been accused of not treating his monkeys well. In the sketch I was an abusive character who was beating his monkeys and the baby monkey at the end of the sketch had had it. I mean, listen to the story, right? I'm basically telling my story all over again. So the baby monkey finally decides to seek retribution and then it turns into kind of a Martin Lewis thing where we're chasing each other all around the theater over seats and through walls and jumping through windows and shit like that. So that was like in the mid-90s. And then we got the TV show where we did more of the same in a show called Monkey Boys. Monkeys are a theme in this.

Max Chopovsky: 25:36

Do you think there's any correlation between your coming to terms with what all of that playground stuff meant in your life and the move away from the more physical?

Brett Baer: 25:48

comedy? Yeah, absolutely. I mean aside from the fact that at a certain age you go like, oh, I can't do that anymore. That's part of it. But yeah, I do think, like I think as I got more evolved and as I grew more to be appreciative of my whole self, new dynamics and new colors came to the forefront. That I think like if you look at the arc of my TV career, for example, mine and Dave's TV career, we started in hard joke comedy, not physical comedy, but like Norm MacDonald, working for two years on the Norm MacDonald show, it was all about learning hard jokes and so we did a lot of hard jokes, sitcom writing. And then, as we get to about 10 years later, we start doing United States of Terra, which is really just kind of like a half hour drama, even though it was called a comedy but it was not. It was way ahead of its time. It was a very dark, very deep show that we ended up show running eventually at the end of the series. And then New Girl was kind of maybe a blend of that because it was emotional and the sort of thing. But by the time you get to Bad Sisters and our being in love with the material that led to Bad Sisters. I think you see more of a complexity in the kind of work we're doing. That I think kind of got less reliant on big, broad, wacky, knockabout stuff and started to get a little bit more emotionally rich, because I think I'll speak for myself I can't speak for Dave, but I just got more comfortable being honest about those parts of myself and the feelings I was having and where I felt like I was succeeding and failing in my life and wanting to explore that and I think that's probably to answer your question a definitive.

Max Chopovsky: 27:25

yes, I mean I think we, on one level, we kind of have to thank those future mafiosos for setting in motion what would eventually become Crazy Monkeys.

Brett Baer: 27:38

Well, that's true. I'm hoping that they had their own journeys and that they all discovered their own fuller selves. And maybe that may. I don't know. I don't know. But again, all I know is what I saw in the news and who I was looking at. I don't know what their involvement was, I just know that it seemed like there was a really tough life. Like. I didn't mention this, but my main bully was actually an adorable little, self-avowed 12-year-old Nazi, and I only call him a Nazi because he called himself a Nazi and I think that he was just mostly angry that he wasn't Italian and it wasn't allowed into the cool club and needed an identity. So he became a Nazi and I'm half Jewish anyway, but he didn't call me half the names, he called me all the names, all the fun names, and he was the main source of pain in my life.

Max Chopovsky: 28:35

So the band leader, the band leader yeah Well, it's interesting because, like, on the one hand, you have them to thank for starting this first part of your career, on the other hand, it's so interesting how, as we evolve and your story touches on this as we evolve, two things happen. One, we realize that other people don't care as much as we think they do Great point. And in parallel, we start to care less. That's exactly right. Just imagine the shit you used to care about and what was so just dominating in your life, the things that would dominate your thoughts. And now you look back on that, you're like not only was that completely irrelevant, but nobody cared about it as much as I thought they did, because they were doing the same thing I was doing, which they were so self-absorbed that they were too busy to even think about what I was dealing with.

Brett Baer: 29:41

One fantastic point. I mean the reality of this is and it kind of goes to the storytelling stuff the reality is everything I just told you is true, but it's true from my perspective, right, like there are other kids who went to Wilmot Elementary School and Junior High and Deerfield High School who did not have this experience, who would say what are you talking about? It was all pretty in pink. I don't know what you're like, you're nuts. So everything I told you, I saw with my own eyes or I heard. But again to your point, max, we blow these things up to this large scale because that's how important they are to us and in reality maybe this wasn't what was happening, maybe it was my perception of what was happening. But what's important is recognizing that we all keep doing this right and as we get older we get better at it. But I think it's human instinct to want to organize and understand and explain and to put the narrative together in a way that helps us think we understand, like, for example, in my story. It's like the reality is I thought I was in control by challenging these kids to do these things to me, but it's like if you take a step back in a larger scale way, in a more spiritual way. I wasn't in control of nothing, like that's sad, that's awful that I would do that to myself to feel okay. And I think if I've learned anything, it's really to try to kind of keep reminding oneself of what you just said. Nobody's thinking about this the way you're thinking about yourself and these things aren't as big Like nothing matters that much yeah.

Max Chopovsky: 31:30

Like you weren't in control of if it happened. You were in control of when it happened, or so you thought, and that you extrapolated that to mean that you were in control, when in reality that was the sort of control that you thought you could have to help you rationalize what was happening. But like to your point, who knows, maybe those bullies had a terrible home life and maybe that was there, like if you you know freaks and geeks. When the girl invites the main character over to her house and it's, the dinner starts totally fine, the parents seem normal and they live in a trailer, but the conversation is completely normal and then it just devolves so quickly into her just screeching out of that parking space and it's like to people that don't know where that girl is coming from, what her home life is like. They're like she's bitch. But then the main character goes over to her house and she was like, oh my God, I'm the only friend she has and this is just her coping mechanism.

Brett Baer: 32:37

Exactly, exactly, I mean there's no doubt. I mean just imagine the pressure you must be under growing up in those circumstances that must lead to measuring up, or who knows beyond that, what was going on. I don't know but something, because why else would you be so?

Max Chopovsky: 32:54

cruel, you know. I mean, that's sort of the evolution, right. If we're lucky enough to get to that level, we start to expand our perspective from just us to those around us. And when you can do that and you can have that sort of empathy, then you start to understand where people are coming from. And I can't remember where I read this, but it was something to the effect of when you see somebody do something, you have to give them the benefit of the doubt, of the most kind interpretation of the action that they're taking.

Brett Baer: 33:27

Ha, that's fantastic. You just described my wife because you know, as you said in the intro, my driving is aggressive. I think is fair to say. But when sometimes somebody cuts me off or isn't driving in a way that I feel is okay and I say my words out loud where I become the bully, my wife will be like that person might be rushing to the hospital because their mother is about to go into surgery and I'm like, why do you tell me this stuff? Leave me alone, right, let me just rant and rave. And she's probably the most evolved person I know and it's like I want to be more like you. But you know, I wonder sometimes too, max, like are there aspects of my personality that are actually copying or mirroring what I was taught on the playground? Do I bully? Are there times when I'm aggressive, or did I learn to fight back in some ways where I'm not the most evolved?

Max Chopovsky: 34:25

person I could be. I think the fact that you're asking the question means the answer is no, Ha ha ha.

Brett Baer: 34:31

Okay, I'll take that.

Max Chopovsky: 34:35

It's like everything everywhere all at once, which I'm sure you've seen. Yep, At the end you fight with hugs and, like after I watched that movie, I literally the next day started like not that I wasn't hugging my kids before, but I hugged them even more. And now, like when we have disagreements or fights or they're you know, being nasty to each other, I'll just come up and come up to them and give them the biggest hug. And it's crazy because half the time it actually works, Like it just sort of dissolves the tension.

Brett Baer: 35:05

Sure, that's so wise and emotionally intelligent I should take that, don't give me the credit.

Max Chopovsky: 35:11

I saw it in the movie.

Brett Baer: 35:14

Oh, okay, I'll credit them, but it works, the Daniels.

Max Chopovsky: 35:19

So you talked about the moral of the story. Is there anything you want to add with respect to what you think the moral of the story is?

Brett Baer: 35:28

Hmm, I guess the moral of the story it's a cautionary tale which is be true to oneself Don't try to be more than you are or you're not. You'll fly too close to the sun and you will burn up.

Max Chopovsky: 35:45

I think that's probably what I would say. We all know what happened to Icarus.

Brett Baer: 35:49

Exactly.

Max Chopovsky: 35:51

Why did you choose to tell this particular story?

Brett Baer: 35:55

That's a great question. You know it's funny because when we were talking prior to doing this and you were giving me the parameters of the podcast, I, you know you go. Everybody thinks like, oh, I've got a great story. And then when you're forced to like, think about one story and go like, well, what story am I going to choose? Like, what story is the story that defines me or that I want to share, or whatever. And it was strange because I think, ultimately, there's a lot of elements to the story that I think I hope anyway, are interesting. One is the stakes are so high because it gets to life and death almost literally. There's a crazy, ridiculous risk factor that most people, in a wish fulfillment kind of way, are going like I would never do that, like who was stupid enough to do that. But then I think the other part of it and I don't always tell this aspect of it when I'm telling the story, because you know I might be telling it to the people I know, who know me, so they kind of have a background on who I am. You know it's one thing to tell a story about a guy who's, you know, a big, tough, professional stuntman who's going to do a high jump for the first time or a high fall, you're not emotionally really invested in that because the dichotomy and the story isn't that strong. I think the background stuff and getting prepared for this podcast forced me to kind of dig in a little bit and kind of go like, okay, well, why did I do this? Who am I or who was I? And it opened up other stuff that I've talked about quite a bit, especially in therapy, about who I am and who I became. That was really connected and so it gave the story maybe what I would call like a bottom note or a deeper layer than just sometimes. Usually when I tell the story, it's like, oh, yeah, I've done high falls, what? Yeah? And I tell them the story and I got hit in the head and people are just like, ah, you're an idiot. I'm like, yeah, I am an idiot. But there is something I think rich in that concept we were talking about that, the things we do to ourselves to survive and I think that was definitely at play here and has been at play in so much of my life, and so I guess that's why I chose the story. It's fun, it has good backstory and I think you're hooked in by the risk and it's got a good payoff, which is that I get you know smacked in the head and don't remember anything.

Max Chopovsky: 38:12

Even though you don't get the part, you get the lesson there you go, look at you, nice, very nice.

Brett Baer: 38:21

You must do this professionally. Ha, ha, ha ha.

Max Chopovsky: 38:25

What do you think makes the story work? Structurally, cause you do a lot of professional storytelling. You understand how a story has to play in order for it to resonate. So, from a structural perspective, what makes it good?

Brett Baer: 38:40

I'd say there's several elements that are really important, and one of them is you have to start with an emotional connection to the story. And when I say emotional, that can like if you're just gonna be funny for funny sake, like a standup telling a story, then you can emotionally connect to people by being hilarious. But what does really help is if the audience is able to put itself in the protagonist's shoes and feel like you know and relate on some human level. So hopefully, the vulnerability of saying like I was a beat up kid and I was like everybody has a version of that and so I think there's some universality there. I think obviously, as I said before, stakes, having high stakes, is always important in storytelling. I think, probably from a TV writing standpoint or dramatic writing standpoint, stakes is really the most important thing of all, because if the stakes aren't high and it's the question you get asked by executives all the time in our business which like what are the stakes, what's the jeopardy, what are we rooting for? And it's all the same question which is like what is the audience clinging to? Like I need this answer for myself Like what hangs in the balance. So I think that's important. I think surprises or escalations, like my story doesn't end with me doing my first high fall. My story ends after the CNN crew shows up and that's like a surprise and an escalation. It takes like, wow, you actually did the high fall, but wait, a second hold on, it's gonna get even crazier. Listen to this. So that adds an element. I think in storytelling you wanna keep turning and twisting. So once you have the stakes in place and the character has his drive to answer the jeopardy and they're on their way, what are the obstacles that come along? Oh, cnn shows up. Or it's not this tower, it's that tower, like. So those turns and escalations are especially in dramatic writing and I assume in all writing, but specifically for what we do in our business, everything, right, that's where you get an act break, like in the old days when you used to do commercial TV and you needed to build to an act break right, whoa, shit, that just happened. Wait, oh yeah, come back afterwards and you'll see what happens now that they're both up there on the platform together with the camera. So turns, escalations, I think, make a good story and then a payoff. I mean, you need a big payoff, you need a climax. It needs to build to something that's worth landing on. You don't want your story to fritter out at the end, it's like. And so then I, you know, I think if I had told the story and then I did my first high fall and guess what, I lived and I succeeded and it went okay. It's kind of like a little flat, a little boring, and the reality is so much more interesting, which is that it goes on from there and it builds to a bigger payoff. So building a story where it starts kind of small and simple, we all can kind of relate to it, and then it turns and it twists and it escalates and then boom, it pays off in some big, funny or powerful or dramatic way or meaningful way, you know, if you can land on something deep, some deep realization or epiphany, that also works too, and maybe especially if it's not a fully happy ending.

Max Chopovsky: 41:33

like you, didn't get the part.

Brett Baer: 41:35

Yeah, exactly, I think there's richness in that. I think you know, there are those well-made endings where it's just like and everything worked out, blah, blah, blah, and then that could sometimes be like ah, that's lovely. The reality of life is and I think we're seeing this more and more in the kind of dramatic writing we're allowed to do, where comedies and dramas are kind of blending. The beauty of that is you get something that feels a little bit more organic and a little bit closer to all of our lives. It doesn't end like a Brady Bunch episode where Jan gets to star in the play or whatever. I don't even think that's an episode, but it should be. You know what I'm gonna write that right now. Let me write that down. But the endings of a Ted Lasso to Succession or you know that were left a little bit more hung in the balance is a beautiful storytelling technique that I think feels like life. It feels like life and also you're not letting the audience off the hook Right exactly, and if you want them to come back, it's a great way to do it.

Max Chopovsky: 42:32

Yeah, I also, as a side note, think that there should be a different perspective. The same story should be told from a different perspective of the CNN cameraman who has never had to climb up one of those towers, let alone with a camera on his shoulder. So he was probably using one arm, and then everybody else that climbed that tower probably jumped off the platform. This dude had to climb back down, knowing that he had priceless footage that he would lose if he dropped the camera or fell. So that dude's stakes were high. And the fact that he did it without even asking, when his producer was like go, I mean props to that guy.

Brett Baer: 43:11

I love this. You're a genius because in 30 years of telling this story I've never thought about that. And he's just the antagonist, the villain of my story. But the fact is he's got a whole life and, like you're right, like he did climb up that ladder, it must have been with one arm, because that camera was on his shoulder. He was holding it up there. I don't know how he did that. I don't know who this guy is. And, right, what if he had his own, you know, cross to bear? You know, and you're right, he probably did have to climb down. I don't remember because I was, you know, basically unconscious and he did have valuable footage of me almost losing my life.

Max Chopovsky: 43:48

Yeah, I mean that guy. Just imagine it was going through his head.

Brett Baer: 43:53

Maybe I need to look him up, go have a beer and say Well, definitely Probably something harder.

Max Chopovsky: 43:59

Yes, yeah, maybe so. So we've talked a little bit about stories. What in your mind, makes for a good storyteller, a good storyteller?

Brett Baer: 44:10

Hmm, well, I'll give you a couple things here. First of all, passion and a desire to share and a willingness to peel back that first outer layer and show and be vulnerable and expose some truths that are the kinds of things that I think all of us in our daily life try to cover up. So I think being able to kind of maybe pull the curtain back a little bit and show the deeper, darker stuff that's under there is rich, and I think audiences like really appreciate that. I think another thing that makes a great storyteller is somebody who is willing to just get out there and fail, like anybody who's like willing to just throw themselves whole hog into sharing and experience and isn't afraid to maybe fall on their face. I'll give you an example of this. This isn't somebody who was afraid to fail at all, believe me, this guy. So I worked on 30 Rock, tracy Morgan. I was on set one day and Tracy comes up to me. I'm just standing there with my script or whatever, and he comes up to me and he goes, and I'm not going to try and do a Tracy Morgan impression, because there's some people that do a very good journey and I don't, but he's like I want to open a restaurant. I'm like, oh okay, yeah, like what kind of? And he went into this whole bit about how he wanted to open a pancake house, where he was going to do a stage show, where he was going to ride one of those like old people scooters and jump like Evil Caneville over phone books while people reading their pancakes. And I was like what is he like? He's clearly out of his mind. But okay, and I was kind of egging him along and he was, he would get more and more detailed about the pancakes and the sort of thing. And somebody else walked over into the conversation and Tracy turns to this person and goes I want to open a restaurant. And he starts this story or this bit or this chunk over again and I was like, oh my God, he's working on material. He was using me to bounce material and so he starts telling the same story as he's doing that. He's self editing, right? Anything I didn't respond to or didn't laugh at he doesn't touch. It's gone. Anything that I did laugh at. He not only says again, gets the same laugh, but then expounds upon it and goes further. And then a third person comes over to the conversation. He turns to them and goes I want to open a restaurant. And then we're right back to the top again and I'm watching him and I'm going son of a bitch, this guy's he's probably got like a Conan appearance or something like that. He's working a bit out and he is brilliantly on the fly determining what's working, what's not, as he tells this story, this ridiculous, silly story. But I'm watching him work and I think that's another part of great storytelling is like, like I said, I've told this story 30 years now and I, you know there are parts of it that I leave out, or there are parts of it that I add in. Or, like when I knew I was doing this podcast, like I said, I thought, oh, dig a little deeper into this. And I think having an awareness of what the audience is responding to or not, like where the heart of what you have to share is actually connecting, and that's something that I think takes practice, which is why I think you have to be willing to fail and you have to be willing to kind of like, try it and it's like okay, the ramp up to the story is too long, let me get to the cool part. Or you know what? I didn't really nail the ending. Is there a more profound or more hilarious way that I can like button this thing up? Where's my out? What's my? Do? I need to like spend a little more time explaining this so that people can follow along and actually get the jeopardy you know Totally.

Max Chopovsky: 47:48

Totally. It's crazy how you can't get better at whatever it is you're trying to get better at unless you are willing to be humbled and be a beginner, because I feel like the older we get, the harder it is for us. We might be growing on one side of things, in terms of understanding who we are and other people don't care, et cetera, but on the other end, we're kind of more and more hesitant to look like beginners because we have all this experience, we've done all these things, we have all these accolades. Why should we look like beginners? But that's what you have to do for growth. And the fact that he came up to you without, by the way, telling you what he was about to do. He just went right into it, which is brilliant, and he just processed what you were telling him and immediately used it, and he was like I don't care if you think this shit's not funny. Maybe you're not my ultimate audience that I actually want to perform this for. Maybe you're just my tester, right?

Brett Baer: 48:57

Yeah, and I'm going to get from you what I can and it's going to be filed into my human computer and I'm going to come out with a new output for the next person based on the feedback you gave me, and I'm going to try it again. You know, I'll say something about your beginner thing. I'll just I'll let you know a little thing. I was terrified to come on the podcast today, because it's scary to put myself out here like this, and I was in a panic but I'm always in a panic about auditions or meetings or, you know, pitches or whatever. So I'm used to it at this point and I've like kind of worked on the muscle of kind of like okay, okay, you're going to go through this process, you're going to go through this, you're going to go down seven minutes before and you're going to go blah, blah, blah, blah. So I have learned to cope with the pain and the fear of failure well enough to actually show up and click on the link to start the podcast with you. But it wasn't easy and I think that's part of the thing too is recognizing you know what it's hard. It's hard to be vulnerable, it's hard to put oneself out there, and if you're going to be the storyteller in a situation, if you're going to try to connect with people, you're going to have to share a little bit and you're going to have to get vulnerable and personal. And then you have to just kind of say you know what, and it's sort of what we've been talking about all along this is me and I'm good enough for me. And you might not like me at the end of the story you might be bored, you might not care, you might think I'm rambling, you might think this, but you know what. This is who I am, this is what I got. Somebody will like it, somebody will love it and it might not be you, but I got to give it my best shot. And then the more comfortable you get with the process of saying I'm going to jump in here and just I know I think I can entertain you. I mean, I think for me that's ultimately the largest goal is entertainment. Because you know you say the moral story. I know you often ask in the podcast like, do it's every story have to have a moral? And that you know I think no, they don't. But you could probably find a moral in any story if you look for it. On the other hand, I kind of subscribe to the Seinfeld approach of like, no hugging, no learning. That it's maybe not our job when we're telling a story or writing a story to proselytize or to teach a moral or a lesson. Our job is to tell an entertainment that then people can derive from it what it means to them, and then somebody's going to have a different opinion or a different takeaway, and that's the good thing. But what you can offer is a human truth that then can be absorbed by the audience, and then that's their business. That's sort of their like. I had English teachers to say chewing gum should be done in the privacy of one's own bedroom, and I'm like what? But maybe deciding what the moral of the story is also something that should be done in the privacy of one's own bedroom, because I think when you write to it you're not doing the fundamental job of capturing an audience and taking them on a ride.

Max Chopovsky: 52:12

Perhaps Correct, and if you're good enough as a storyteller to write a story that has that bottom note, then you don't need to sort of cram the moral down the audience's throat, because different people might come away with different morals. Some people might not see a takeaway at all, and that's okay. What is one of your favorite books? That is a really good story that gets storytelling right.

Brett Baer: 52:43

Well, if you don't mind, I'm going to cheat a little bit. And it is a book, but it's a play. It's a book. That is a play that I read when I was in high school. I found it in my high school public library, which is stunning to me in this day and it brings Chicago back around again too which is American Buffalo by David Mamet. Which the thing about David Mamet that I fell in love with as a kid, besides all the swear words, which are just beautiful, luscious sentences of foul mouth genius, but what Mamet gets so right and is such a, by the way, I want to say, I know that politically and otherwise, david might be sort of like a lightning rod right now, but let's just talk about the work. I don't know the man. The writing is so lean and so tight and so unfat that reading and understanding American Buffalo or Glengarry Glen Ross, especially the stage version, is such great tutelage in terms of getting to the point, cutting what's unnecessary, leaving the audience to fill in the blanks, the pauses, like the pincher pauses that Mamet adapted. We joke about pincher pauses, but it's like what's not written becomes what is written. And I'll tell you, I'll give you a quick story real quick. When I was a senior in college I was like what am I going to do with my life? David Mamet was my idol. I was like I'll go work for David Mamet. And so I wrote David Mamet like a six page letter just gushing about how important he was to me, and I sent it. I got an address for a movie he was working on called Things Change, and I sent him this six page letter Please, if there's anything that I could do for you, I don't even need to get paid blah, blah, just use this, use that, use that. It was on and on and on. So about a month later I come home to my rental house at USC and I open my mailbox and inside is a letter with the Things Change stationery, and typed up in the upper corner is just the word Mamet. I freaked out. I was like oh my God, like you could I still have the letter, obviously. And the envelope, which you can see, I ripped open as if I was like yeah, so the letter. Basically, I'll quote it to you, it won't take long. He says Dear Mr Bear, thank you for your kind note. Unfortunately, I have no position to offer you at this time, but I appreciate you writing and wish you luck in the future. Sincerely, david Mamet. And to me, that was my first lesson in writing that came at the hand of David Mamet, which was dude I didn't need six pages and the fact that he wrote back at all. In my silly little mind I take a lesson from it, from Mr Mamet. He might have just been like I'll write the kid a note, but to me the lesson was calm down, just keep it simple, stupid.

Max Chopovsky: 55:54

Get to the point, get out, write six pages, sleep on it and then convince it to three, sleep on it again and then cut it in half until you have a half a page and you'll realize how much superfluous shit it was in that original six pages. Oh, I'd be embarrassed to read what I wrote. I mean, that is normal for a creative. When you read V1, when you're on V4, you're like, oh my God, that was dog shit. In fact, I once flew to New York for the day to see Glenn Gary Glen Ross when Al Pacino reprised his role and I waited for him out back with the program and he signed it for me. Oh, how cool. I just remember because I am such a big fan of the dialogue in that movie. Along with so to me it's the three finance movies Glenn Gary, glen Ross, wall Street and Boiler Room, and this was before Billions, right. So it means fantastic, fantastic, really tight dialogue and just to see Pacino up there, it was, oh my God, it was worth every. It was unbelievable.

Brett Baer: 57:03

I saw Peter Falk play the Jack Lemon role in Chicago on stage. Yeah, oh, and I don't know if you know this, but this is another writing thing too. But you know that Alec Baldwin monologue from the movie was not in the original play but it was so successful, became such a powerful kind of memorable moment that Mammet then incorporated it into the stage play. But it is not in the original Pulitzer winning theater piece. Wow.

Max Chopovsky: 57:30

He pulled the Tracy Morgan.

Brett Baer: 57:32

Yes, he did Exactly. Hey, that's working. I'm going to put it in, yeah.

Max Chopovsky: 57:37

Last question for you If there is one thing you could say to your 20-year-old self, what would it be?

Brett Baer: 57:46

Oh boy, relax, have fun, have faith, trust. It's all going to be okay. You'll get everything that you're meant to get and there's no sense fighting for the things you think you were meant to get that are not your destiny. So just have a good time and stop worrying and angsting so much. It's all going to be fine, you're going to be okay.

Max Chopovsky: 58:20

Enjoy the ride. Yes, enjoy the ride For what it's worth. It is never too late for that advice for anyone listening ever.

Brett Baer: 58:31

Yeah, I'll tell you, from my ripe old age of almost 57 now, I'm still teaching myself that every day. Or when I say teaching, trying to teach, I should say because I'm not learning, I'm still angsting.

Max Chopovsky: 58:46

Most important thing is the effort. That's all part of the journey. Well, that does it, my friend Emmy, Award-winning producer and writer Brett Baer. Thank you for being on the show.

Brett Baer: 59:00

Thank you, max. I had a great time. You have the best voice in podcasting, so soothing.

Max Chopovsky: 59:05

I appreciate it For show notes and more. Head over to MossPodorg. Find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, wherever you get your podcast on. This was Moro of the Story. I'm Max Jepowsky. Thank you for listening. Talk to you next time. Thanks for watching. I'll see you next time.