44: Delia Cohen

Source: Instagram

“And then my friend did it. She Googled the names of the two incarcerated organizers to find out about their crimes.”

About Delia

Delia Cohen specializes in turning extraordinary ideas -- involving the arts, cutting-edge technology, and new media -- into reality. The common theme of her projects? They all attempt to make the world a better place.

She ran the messaging department at the Clinton White House during impeachment and transition; helped organize the first and second Clinton Global Initiatives; produced Richard Avedon’s last work, a photo-essay on democracy for The New Yorker; rebranded Goldie Hawn’s education foundation; managed Nokia’s $1 million global investment challenge; and pulled together in 15 months an extremely ambitious TED Prize project – a global film event called Pangea Day. For most people, that would be a lifetime of work. But for Delia, it was just the appetizer. Her main course – her magnum opus – would be on another level entirely.

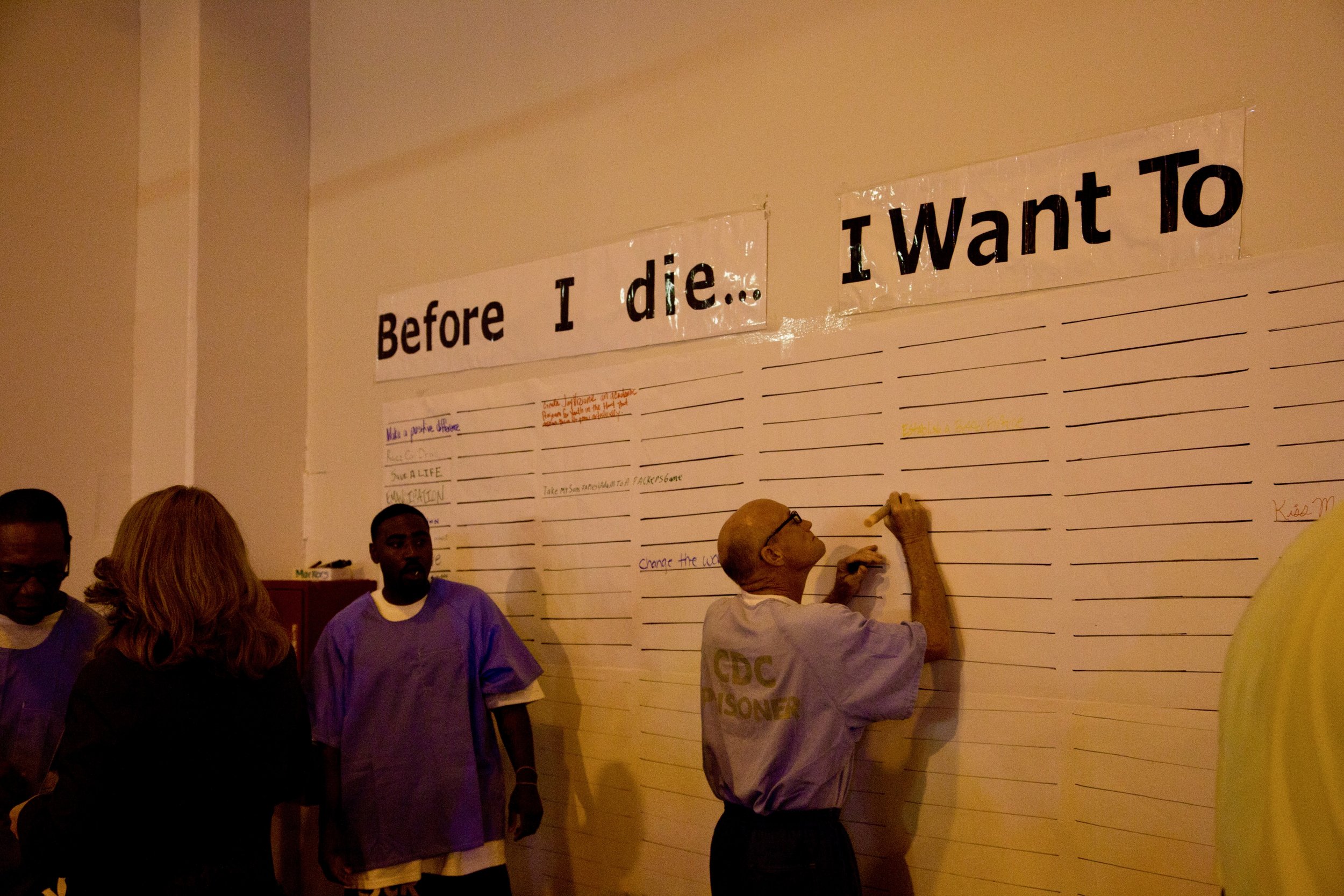

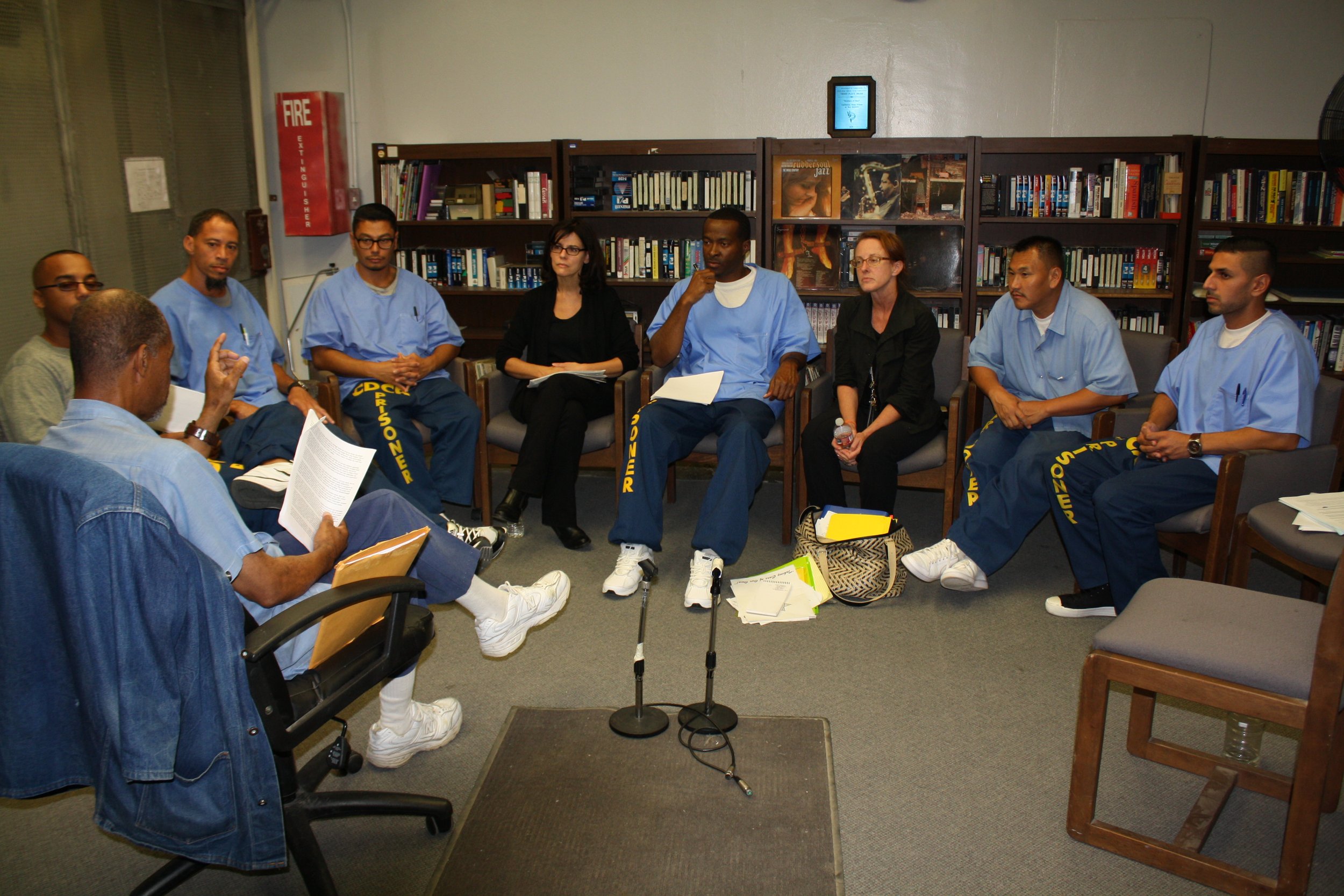

Delia’s most interesting, challenging, and rewarding work has been in criminal justice reform. For the last decade, she’s been leveraging her unique network of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people, correctional leadership, activists, entertainers, and entrepreneurs to organize TEDx events in prisons around the United States.

With Delia’s guidance, incarcerated people, correctional officers, prison administrators, and community members collaboratively plan and curate each event. Following Bryan Stevenson’s call for advancing justice through proximity, half of the attendees are community leaders and half are incarcerated.

Numerous attendees have found the experience unforgettable and transformative, spurring a wave of criminal justice activism and philanthropy. Shared on the TEDx YouTube channel, videos from the prison events have gone viral across the globe and comprise an unprecedented archive of authentic voices and ideas for criminal justice reform.

When she’s not working at a prison or meeting with high level dignitaries, Delia retreats to her upstate New York 18th-century Dutch Colonial farmhouse, where she lives with her dog Buddy.

Books

Just Mercy

-

Max Chopovsky: 0:02

This is Moral of the Story Interesting people telling their favorite short stories and then breaking them down to understand what makes them so good. I'm your host, max Chepofsky. Today's guest is Delia Cohen, who was introduced to me as somebody whose philosophy, work and impact takes her breath away. Cryptic intro I'm in. I joined our call ready to learn, and she was a no-show. I thought to myself really, we had this on the calendar and everything. What happened when Delia got in touch later that day to apologize for missing our call? Her excuse was that she was in prison, and would I mind if we got another time on the calendar? In the blink of an eye, I went from frustrated to humbled, guilty and extra intrigued. This was going to be good. So let's talk about Delia. She specializes in turning extraordinary ideas involving the arts, cutting-edge technology and new media into reality. The common theme of her projects they all attempt to make the world a better place. She ran the messaging department at the Clinton White House during impeachment and transition, helped organize the first and second Clinton global initiatives, produced Richard Avedon's last work photo essay on democracy for the New Yorker, rebranded Goldie Hawn's Education Foundation, managed Nokia's million-dollar global investment challenge and pulled together in 15 months an extremely ambitious Ted Price project, a global film event called Panjiode. For most people that would be a lifetime of work, but for Delia it was just the appetizer. Her main course, her magnum opus, would be on another level entirely. Delia's most interesting, challenging and rewarding work has been in criminal justice reform. For the last decade she's been leveraging her unique network of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people, correctional leadership, activist entertainers and entrepreneurs to organize TEDx events and prisons around the United States. This is what she was working on when I joined our call, and this fact was a swift reminder for me to chill out, give people more grace and apply the most generous interpretation of their actions. With Delia's guidance, incarcerated people, correctional officers, prison administrators and community members collaboratively plan and curate each event, following Brian Stevenson's call for advancing justice through proximity. Half of the attendees our community leaders and half are incarcerated. As a side note, if you have not read Brian's book Just Mercy, put it on your list immediately. Numerous attendees have found the experience unforgettable and transformative, spurring a wave of criminal justice activism and philanthropy Right on the TEDx YouTube channel. Videos from the prison events have gone viral across the globe and comprise an unprecedented archive of authentic voices and ideas for criminal justice reform. When she's not working at a prison or meeting with high-level dignitaries, delia retreats to her upstate New York 18th century Dutch colonial farmhouse where she lives with her dog, buddy. Delia, welcome to the show. It is an honor to have you.

Delia Cohen: 3:15

Thank you, max. It's so wonderful to be here and thank you for that lovely introduction.

Max Chopovsky: 3:20

My pleasure. So you are here to tell us a story, set the stage. Is there anything we need to know about the story before we get into it?

Delia Cohen: 3:32

I guess it would help if everyone knew the difference between TED and TEDx. Do you know the difference?

Max Chopovsky: 3:39

Yes, tedx are local, community-organized events, whereas TED is sort of the big organization. Is that correct?

Delia Cohen: 3:46

That's exactly right. So my story starts four years after TEDx went into practice. So TEDx is the local franchise. It's independently organized TED-like events organized by the community. And TED was surprised, after four years of this TEDx experiment, at how popular it had gotten. But they weren't sure exactly what the TEDx organizers were trying to achieve for social change with the platform. Why were they having these events? Basically, they had a website that was full of videos from the events, but they didn't know what the organizers were trying to do. So the head of TEDx, laura Stein, hired me to look at who were these TEDx organizers around the world and what were they trying to accomplish for social change in their communities, and with the idea being that if anything really resonated with TED, maybe they would help implement some of these ideas. An example being there happened to be a robust TEDx community in some slums outside Nairobi and the TEDx organizers did not have electricity. So IDEO who's a lot of IDEO people go to TED. They designed a TEDx and a box kit for the TEDx organizers. No electricity, and Bill Gates and Melinda Gates and the Gates Foundation actually paid to have the kits distributed to TEDx organizers around the world without electricity. So I was looking for things like that and I read a blog post that TED did and realized that three countries had held TEDx events in prisons. And I knew nothing about prisons and this was the end of 2012. I'd never been in a prison, but I was thinking who on earth in prison is watching TEDx, let alone having events? Who's speaking, who's attending? And Spain and Moldova had done little things. But then I get to the organizer of the prison event in the United States and it's this college student in Ohio, and I email her to ask if we could set up a meeting and she said, oh, but the two main organizers are incarcerated and we have a conference call at the prison. And I was very intrigued and I said, of course we could. And so we had an hour-long conference call with the two male incarcerated organizers, their re-entry supervisor, who was also on the phone, and this college student from Ohio State, and they explained to me that these two men had gotten addicted to TEDx and found out that nearby Ohio State University, which was near the prison, had been having TEDx events there. So they found the organizer, this college student, and asked her if she would come over to the prison and help them figure out how to hold a TEDx event in the prison, and so they had done this. I think I was talking to them in January of 2013, and the previous, september 2012,. They'd had their first event, and they said they wanted it to show a 360-degree view of the criminal justice system, so it would involve both incarcerated people as speakers as well as prison administrators. It would involve survivors of crime and law enforcement, and half of the audience would be outside community leaders and half would be incarcerated people from the prison. And so we had this fascinating call and I got right off the phone and I was thinking everybody in prison lies. This can't really have happened. And I went on YouTube and I looked and, sure enough, there was the former attorney general of Ohio talking about how he had become a death penalty advocate in his life, and then there was an incarcerated guy talking about his journey, and then there was the head of corrections for the state of Ohio talking about something, and then there was a prisoner, and then there was the warden, and then there was a prisoner doing a poem. And I was just like this is amazing. And so this was January of 2013. In April of 2013, they were having their second TEDx event and I was still working on this TED project. So I ended up for work, going to prison for the first time to a TEDx event, and because I was from TED, they let me in first of all the guests. And so I walk into this room. It was the religious activities area and I was surrounded by the sea of men wearing blue and I just froze. I was like where are the guards? This is scary. And the incarcerated men were so welcoming and so nice. They were just lovely hosts and they're like hi, how are you, where have you traveled from today? And helped like move me out of the corner where I was frozen in the room. And that was the only time I was scared. The rest of the time I just was involved in incredible conversations and I could not believe. Throughout the day I mean more than the talks, which were great, but I'd heard great talks before. It was the breaks and it was interacting with so many men who were so interesting and who I was having such an enjoyable time talking to. I had arranged with the prison to spend the next day at the prison as well, after their day long event, interviewing everybody from the head of security. So I was curious what if a prisoner suddenly goes rogue on stage? Do you cut the mic or what's your security plan? So I was interviewing the warden. What made him feel comfortable doing this? How did they decide what outside guests to allow the incarcerated men? What were they getting out of it? And so I spent the whole day and I just got more and more and more excited and inspired and I thought, oh my gosh, this like to have authentic voices of people who live and work inside prison on something so established and globally recognized like the TED platform. That would be amazing. Why don't I, since we have a quarter of the world's prisoners in the United States and these guys have this great idea but they're incarcerated why don't I try and spread their idea all around the United States to let other people have this opportunity that I have and I'm having and I'm so enjoying? And it was just like all these assumptions I had had about prison that I didn't even realize I'd made. I was being challenged right away. So, anyway, I was absolutely excited and got in my rental car to go to the airport and fly home to San Francisco, and I was driving, my friend was sitting next to me. And then she did it. She Googled the names of the two incarcerated organizers to find out about their crimes. And of course I have to say I had been insanely curious the entire time I was there about what everyone had done to get there. And there was only one person that I'd actually spent enough time with over the two days who was kind of my guide. It wasn't one of the two organizers because they were so busy at the event, but it was this incarcerated man who seemed like a leader. Everybody seemed very respectful of him and I guess he had started this great mentoring program. So he's the only one I discussed his crime with and he told me that he had a drug dealer threaten his family and he killed the drug dealer is what he told me about his crime. So anyway, there goes, my friend, and she is Googling, starting with the two incarcerated organizers, and it turns out, as the newspapers reported, one of them when he was 17, either strangled or beat to death, his 14 year old girlfriend, hit. The body was from a very like good background, from a well to do area. Nobody suspected him. He had Christmas dinner with her family while she was missing and it turned out he was caught and he was reported to have just wanted to see what it was like to kill somebody. And then the other organizer was described as a sexual predator and I was just shocked. And even so, she then Googled the guy who talked to me about his crime and it turns out the drug dealer was a woman, which shocked me. I had just been picturing this male drug dealer like threatening his family, but he killed a woman drug dealer which so I quickly was facing the realities of the people that I was thinking I wanted to work with, that had done horrific things. Anyway, I flew home completely crushed. I mean, I was in such a deep depression. I kind of went into my bedroom and just slept for two days. I just I had no one to talk to about this. I couldn't talk to the men who organized this. It was just awful, but fortunately so. I was living in Oakland, california, at the time and a nearby prison is San Quentin State Prison and strangely enough they were scheduled to have a TEDx event at that prison and I'd gotten in touch with the organizer and said that you know I lived in the area and I'd love to help, so she had gotten me able to go into San Quentin with her. So a couple of days after I got back from this Ohio prison event, I went into San Quentin State Prison for the first time with her to meet with her TEDx group of incarcerated men and I was telling them about my other you know this is the second time I'm in prison, my second prison I've ever been in and I told them about how shocked I was when I found out about the crimes. And how do you have a TEDx event where you build all this goodwill and then the outside guests go home and Google and how do you stop them having the same reaction that I had and freaking out about the crimes? And so they said, well, those were particularly onerous crimes and we're talking about it and it was feeling very healing being there. And also on that first day I was privileged to go to. San Quentin has this wonderful program called the Victim Offenders Education Group, where they have incarcerated men meet in a circle for over a year, sometimes I think as much as three years, and they have not the victims of their own crimes, but they have people who were victims of crimes that come in there and talk about how crimes have affected them. And they do all this work on themselves, and so they allowed me to sit in on a circle. That first day I was in San Quentin and I go into the room and all the seats are taken except one next to this enormous black guy who is just glowering, and I was scared. But I sat next to him and he was bald, his name was Curly and anyway, again being in this group of people, they quickly put me at ease. We went around and said how we were doing. We all checked in and it turned out it was one of the guys was getting out, so it was his last time in the group. So they did a lot of like summing up, which was great for me to hear, being a newcomer. Like one guy had been in prison for vehicular manslaughter, so he was drunk driving and he killed somebody, and another one of the incarcerated people had had a family member killed by a drunk driver and there had been a huge amount of tension between these two people. But gradually through the group they'd come to know each other and appreciate each other and it helped heal some of their feelings. And then the exercise for the group was to read a letter to that you write to your victim. And so, to my surprise, curly stood up and he read this letter. He wrote to the mother of the woman he killed and it was one of the most moving things I've ever experienced in my life. He pulled no punches and taking himself to task for killing this person and hurting his whole family, and it was the most vivid display of empathy I'd ever seen. Anyway, it was quite a first day at San Quentin and I came back a little bit healed from the trauma of finding out the crimes of all those men from Ohio and I decided what I wanted to do was see if I could get permission to have a dialogue with the two organizers who's neither of whose crime I could begin to wrap my head around. I was a sexual predator killing your 14 year old girlfriend just to see what it was like to kill somebody. So I talked to the warden of the prison and said why I wanted to do this. I said I really want to help spread this TEDx program in prisons. But what if everybody has the same experience as me? Can I have permission, if these guys will allow it, to talk about their crimes with them? And the warden said, sure, just promise me one thing and I said okay, what is it he's like? Don't fall in love with them. I said I don't think that's what we have to be worried about at this point. So anyway, I wrote them an email and sent it to their reentry supervisor, who'd been on the call with the original call with me, and told them how impressed I'd been with their work the TEDx event was amazing and that I left the prison brimming with possibilities about spreading their idea all over the place. And I said then it happened my friend Googled you and read me about the crimes and I explained sexual predator and what I'd read about the other one. And I said what's to stop everybody in the audience from having these same reactions? Why should we care about people who've done such monstrous things? I said I know it's none of my business and you might not want to do this, but would you be willing to have a dialogue with me about your crimes so I can try and work through this with you? And they both said yes. So then I had to prepare for a phone call with them where I talk about and I didn't know these guys at all because I barely spent any time with them at the event because they were so busy and so I was researching rape in nature and all these things, trying to prepare for this call and I was so apprehensive about it and it was incredibly awkward. So I just felt like, who am I to be asking about this stuff? They understood why I was doing it and they supported that and, frankly, they said they were surprised by my reaction because, first of all, we're talking over 20 years ago. I was looking at what had happened and been reported 20 years ago, so it was incredibly painful and personal and I felt like I was doing something wrong talking with them. But they clearly really wanted the TEDx thing to be spread to other prisons because they thought it was having such a beneficial impact on them. So they went ahead with it and we did a combination of calls and emails but at the same time, we started working together because I was already planning on like I was working on their next event with them, in which we invited Piper Kerman, who had never been to a men's prison, to come speak. So we weren't just talking about their crimes, we were also starting to work on another event together and on a plan to spread this around and eventually, like I got to know them as colleagues, and although I never did fully understand exactly how they came to commit their crimes, that became much less important to me, and the working relationships that I had with them as who they were today was much more important to me, and the question about them 20 years before became less and less pressing.

Max Chopovsky: 21:43

I mean, it's certainly a testament to people's ability to change. What I'm curious about is you know, pick either the Ohio prison or St Quentin. But what was it like going into a prison for the first time? What went through your mind? What were you thinking? What were you feeling?

Delia Cohen: 22:04

Honestly, it was pure fear the first time. I was just thinking all these people have done horrible things. They've done something in common that they have. They've all been convicted of violent crimes and I am now unprotected among a lot of people who've committed violent crimes. This is really really scary. But, as I said, that didn't last very long at all, because the minute I started talking to these men and same in St Quentin, it's like these are just people and these are really interesting people, and these are people who've done a lot of self reflection and are now like the leaders of the prison and I mean the leaders of rehabilitation, not the gang leaders of the prison, although many of them had been the gang leaders of the prison and had left gangs. So both times, in the Ohio prison and in St Quentin, I just found myself surrounded by really fascinating people.

Max Chopovsky: 23:12

How many of these talks have you done?

Delia Cohen: 23:15

I think there's been about 23 and I've been involved to various degrees with them, so I've done about 12, I think that I've been completely involved in.

Max Chopovsky: 23:30

Across how many prisons?

Delia Cohen: 23:32

Oh, 12 prisons.

Max Chopovsky: 23:33

Oh, wow, okay. So do you remember a particular moment when you realized how much of an impact this was having on whether it's a prisoner, or maybe even a prison guard or another employee at the prison? Do any moments come to mind where you realized, wow, this is really making a difference?

Delia Cohen: 23:58

Yeah, in each of my events I like to have one guard, or corrections officer, as they're called become part of the group, and each time when that happens, it's amazing to see the prison guard cheering for the prisoners who are talking and fist bumping them as they come off the stage, which is just unheard of. In the last prison event, a guard and a prisoner actually took the stage together and talked about how they overcame their mutual like the stereotypes of the other to understand and work better with you know, the prisoner with the guard and the guard with the prisoner, and they just took turns talking and they called it smooth days because it's in both of their interests to have smooth days and get along.

Max Chopovsky: 24:57

Interesting and it says so much about the impact that this program is having. Because you know the Stanford Prison Experiment where they dressed up some kids as guards and some kids as inmates and they had to cut it short because they got so into their roles. And that's an experiment right For these men, it is their daily existence and so the path of least resistance I mean this is a cynical perspective on humanity, but the path of least resistance is for the correctional officers to embrace that power, and I'm sure some of them do. But the approach that the guard took, that took the stage with the prisoner, or the guy that was fist bumping the inmates as they came off the stage, that is the more difficult approach, I would think, and yet the events are allowing them to get their minds into that space where they can do that.

Delia Cohen: 26:00

Yeah, I think maybe the most impactful thing I did a TEDx event at San Quentin. The organizer dropped out and I ended up taking it over and we did it in 2016. Gavin Newsom was Lieutenant Governor at that point and he came. His staff asked me what I wanted him to do and I said just attend, we have too many speakers, could he just attend? And so he was totally pleased to attend, and with no speaking role or acknowledgement. Three years later, in 2019, he's the governor of California and I get an email from him and it was Delia. Just an FYI, I just decided to commute the sentence of one of the incarcerated speakers from TEDx San Quentin. Had I not met him at that event or heard his talk, it would have made a tough decision a lot more difficult. Just an FYI, I was like, oh my God, that's amazing. And the title of the guy's talk was Am I Really a Violent Criminal? And he told his whole story and he wanted people to rethink how they classified people as violent, because it was this tiny little Vietnamese guy whose nickname at San Quentin was the professor he was the farthest thing from he had committed a violent crime, kind of by accident. Anyway, I was so excited that when I got that email it made everything. It's like, wow, if that can happen, that is just the coolest thing ever. We need to have all the parole board members come to these events.

Max Chopovsky: 27:42

And that would help increase attendance among the inmates as well. I'm sure if they know that this could you know this is a possibility. Now I know that you know California not to get into the criminal law too much, but I know that California has this really onerous three strikes law, and so a lot of the prisons are super crowded because there are, you know, a lot of nonviolent offenders in these prisons, but there are still a number of violent offenders. And so having been in so many prisons and met so many people that are incarcerated for, in some cases, life, I'm sure how has it changed your perspective on people's capacity for change?

Delia Cohen: 28:30

Well, it's funny because first of all, I thought TEDx was a terrible idea. I thought it was going to tank the brand. I thought there's no way we can entrust the brand to outsiders. And then, if anybody had ever predicted that I would be doing TEDx events with people who had committed violent crimes and were serving life sentences, I would have said you are crazy, that is not a population I see myself wanting to work with. But it turns out that people who've committed violent crimes and are serving life sentences are the leaders in each prison. Because, I mean, it could be as simple as they're not going to get out unless the parole board lets them out. So they have to take certain programs in order to show that they're changing. And even if they're just taking them so they can get out, education is transformative and once you start taking these programs you can catch the education fever and completely grow intellectually and change. So the people that are most rehabilitated in each prison are those serving life sentences for violent crimes, who've been in for a long time, have taken lots of programs, done lots of work, are changing and all they want to do is help young people avoid making the mistakes that they made so often when they go out into the world. That's what they work on mentoring youth, which is wonderful, and because they're so authoritative, having done crime, spent years, decades in prison, so they can have a tremendous impact.

Max Chopovsky: 30:13

What about lifers without the possibility of parole? Do you see any difference there?

Delia Cohen: 30:18

Difference is that sometimes those people aren't eligible for programs because people feel like it's a waste to, if there's limited resources, to give people who are never getting out the benefits of an education, which I feel is completely wrong. And I would like to do away with life without the possibility of parole. I think everybody should have the possibility of parole and the idea that they can change. I mean, we just let we Governor Newsom and the parole board just let out I'm blanking on her name, but one of the Manson women. She just got out after serving 50 years and the parole board had found her no longer a threat to society. But every governor kept, including Newsom, kept taking it away, rejecting her parole, and he finally let her out and the idea is that you're no longer a threat to society and you've served your time, you've paid your dues. But really people are all about punishment and it's not about the really afraid of letting these people out in society. They just want them to continue to be punished, which is very expensive.

Max Chopovsky: 31:37

Incredibly expensive and letting them out. It's really challenging. The longer an inmate is in prison, the more challenging it is for them to reacclimate to not having every part of your day planned out and having this freedom. And, from what I've read, that is a factor in some of them sort of relapsing, so to speak, because it's I mean, if you've been in prison for 50 years, the world has changed entirely and you don't really have a memory of what it's like to have complete, actual freedom. And then you start to worry about things that you never had to worry about, like how am I going to pay for my next meal? Where am I going to sleep? You know it feels like that's a real challenge.

Delia Cohen: 32:22

It is a real challenge, but the recidivism rate for people serving life sentences is very, very small. People rotate through when they have determinant sentences and they just get out. Whether or not they just go on the yard and smoke pot, you know every single day, they don't have to do anything to get out. Those are the people that keep cycling through.

Max Chopovsky: 32:46

I see Are the events live streamed at all.

Delia Cohen: 32:50

Never have been. So I was just in California this year and they talked about doing that, which is super exciting.

Max Chopovsky: 32:57

Exciting, also kind of risky.

Delia Cohen: 32:59

In the decade that I've been doing this, there's never been one prisoner who's gone rogue. In fact, the only time we ever had to edit a talk, it was Outsider who was quoting a statistic about the Department of Corrections, and they said they had the wrong number.

Max Chopovsky: 33:15

So you mentioned when you entered that first, the first room that was packed and you sat next to Curly, you mentioned the room was packed. How do they select what inmates attend the talks?

Delia Cohen: 33:30

Each person does that differently. Sometimes they do it like Ted does, where you have to write an essay and say why you want to be part of this event. Sometimes they just open it up to people Just putting their names in. First come, first served. Sometimes they do it by if there are a lot of different groups, they'll just take some of the groups, people that have been doing work. Sometimes they'll have younger prisoners in among the population, so they'll try and have it be. Have some younger prisoners that can use it as a good example of something to strive for. It changes at each place. Interesting.

Max Chopovsky: 34:19

Interesting. Let me ask you this, so, as you think about the story that you told, what would you say is the moral of that story?

Delia Cohen: 34:28

I think it's a couple of things. I think the moral of the story to me is that there are no simply good or bad people. People can do monstrous things. That does not mean that they are monsters and that does not mean that that's all they are through their whole life. And Brian Stevenson, who we both love, he says he believes that when somebody is a killer they're not just a killer, when somebody steals something they're not just a thief. And I totally believe that and that's why I was able to get over my problem with the two guys' crimes, because our relationship became so multi-dimensional and I didn't have to fixate on this thing that I read that did not encapsulate all the trauma that they both went through growing up and that contributed to them being able to do those crimes. And as I became more friendly with those two guys, I did learn really intimate things about their lives and their pasts and could kind of understand how they came to commit those crimes which I couldn't imagine being able to understand before.

Max Chopovsky: 35:49

Yeah, I mean you mentioned some of the trauma that they went through, and it's a common refrain, obviously, with a lot of people that commit violent crimes. It almost makes me feel like their parents or their caretakers guardians, whatever the case might be should be held criminally responsible, at least partially contributory negligence, with respect to what they've created out of this human. That at the time maybe not now, but it just makes me feel like some of the blame should rest with some of those caretakers.

Delia Cohen: 36:24

Yeah, a lot of prisoners were in foster care. I would say that. I mean, what I've noticed from working for a decade in our prisons is that it's an incredibly racist system. Almost all the prisoners are black or brown. It's so disproportionately it's unbelievable. And most of them are from impoverished backgrounds and there's so much trauma. I spent my first year honestly working in the prisons. Every time I was driving home from the prison the first year I think I just wept because I just was full of so much trauma from what I've been hearing all day long. And also it's unnatural to see people, people, human beings and then coming to care about human beings living in cages. It's really hard to assimilate that. I don't know how corrections officers can deal with their jobs. I mean, corrections officers have one of the highest suicide rates, if not the highest of any profession in the United States. It's unbelievably hard to do that and where I'm from in upstate New York, there are a lot of prisons and so it's a common thing for people to be prison guards and it's a super hard job.

Max Chopovsky: 37:50

I mean, you just have to be incredibly emotionally calloused, I would think, because if you can't be numb to what you're seeing every day, you can't really do your job.

Delia Cohen: 38:01

Right and I have to say I became more emotionally calloused. I do not cry on the way home from prison anymore, but that first year was really tough and I was thinking I need to learn Reiki or something, because I'm getting all this trauma from other people stuck in my own body. It was just so hard. But I also find that prison is the most optimistic place I've ever been because if in this horrible, horrible place people are transforming and becoming better people, it just makes you think that anything can be possible. The talk that has gotten like on Ted's YouTube channel, tedx's YouTube channel on Tedcom it has over 10 million views the most popular of my prison talks. The title of it is how I Learned to Read and Trade Stocks in Prison, and it's this great story.

Max Chopovsky: 39:00

Yeah, I mean. It's certainly a testament to the power of the human spirit, right? If nothing else, do some of these inmates know that their talks are going viral?

Delia Cohen: 39:10

Oh yeah, like this guy, wall Street, who did the talk I was just referencing. He got letters from all over the world from people. So yes, they do.

Max Chopovsky: 39:23

So, having been at the Clinton White House during some fairly tumultuous times, you had to hone your storytelling skills. Have you found yourself using or leveraging any of that experience in some of this work that you've been doing?

Delia Cohen: 39:45

Absolutely. I am the speaker coach for all of these events, so for the outside speakers as well as the incarcerated speakers and the staff, so constantly giving advice about storytelling and how to think about your audience, how to segment your audience into who's going to be cheering you on, who is the power to make your idea happen, who's going to be putting up roadblocks, and naming all those different segments and then making sure that you're addressing each of those segments in your talk.

Max Chopovsky: 40:23

That's fascinating, so talk a little bit more about that. What are some of the most impactful tips on storytelling that you've been sharing with some of these inmates?

Delia Cohen: 40:34

Well, let's see I talk about. There's something called a star moment where Bill Gates did this once he was at TED and he was talking about malaria and everybody, including me, was kind of nodding off and it just wasn't relevant. So he reaches down and he takes this glass jar of mosquitoes and he's like why should people in Africa be the only ones worried about this? And he opens it up and lets the mosquitoes out and there's this huge gasp in the audience and he's like of course those weren't malaria infected mosquitoes, but all of a sudden we were all paying attention to him. So that was one thing. And then Brian Stevenson did something amazing he made TED is still. It's changing, but it's still mostly like a white elite male conference. And back when Brian Stevenson gave his talk, more so so. But he found a way to make the plight of poor black and brown incarcerated people relevant to white people. He did it in a number of ways, but one thing he did was he told a story about how he was in Germany giving a lecture about the death penalty in America. And he says this woman from Germany comes up to him afterwards and says what you're saying is so upsetting, we could never have the death penalty in Germany. With our history I mean it just never could be. And Brian Stevenson said yeah, imagine, imagine if Germany had the death penalty today and was disproportionately executing Jews. It would be unconscionable, it'd be unbearable. But yet America, with its legacy of slavery, is doing just that disproportionately executing black Americans. And somehow there's this disconnect and we don't talk about it. And just by doing that, one completely new comparison to the Holocaust was able to make this story more relevant to all the Jewish people in the audience. So again, I think my biggest tip is audience segmentation. Who is the power to help make your idea possible? Who is the power to hinder it? Let's label those groups and then identify their objections and try and help get them over those hurdles so they will adopt your idea.

Max Chopovsky: 43:17

You really have to do a lot of homework on that, because it's not like they're going to voice their objections to you. You just have to assume, based on your segmentation exercise, that you know what those objections are and build the responses to those objections into the talk smoothly.

Delia Cohen: 43:30

Exactly Yep.

Max Chopovsky: 43:32

Fascinating.

Delia Cohen: 43:34

You asked about the moral of the story and I was saying that it's about there are no good or bad people. There are just people who can do good and bad things, and they feel like we all have an infinite capacity to do bad and good. But I think the other side of it is judgment is that we judge people. We judge people so quickly and, for instance, now, having worked in prisons for a decade, I know that if I were going to hire somebody coming out of a prison, I would want it to be somebody who served a life sentence. Now my judgment is going to be different than other people's because I know more about this population. But why I want people to come to my prison events is I want them to meet these people, and it is transformative in that you all of a sudden realize you just spent a day with people who've killed other people and you really found them intelligent and entertaining and inspiring and you just wouldn't think that that would be possible. But it absolutely is and it happens at every single event.

Max Chopovsky: 44:50

And it really messes with your worldview it does.

Delia Cohen: 44:56

I told you I didn't like the idea of TEDx and why I'd want to devote time to people who've done bad things when you could be helping children or something. It's not something I planned on, but I stumbled upon this world and then was like, oh my God, it's nothing like I thought it would be and we have a real problem in this country with over-incarceration and the racism of it all, and I feel so privileged. I feel like an ambassador to an invisible country and I want to bring all the people that I love and everybody of any influence into this world to see what it's really truly like not like the movies.

Max Chopovsky: 45:39

Yeah, oh my gosh, I can only imagine. Does every story have to have a moral?

Delia Cohen: 45:46

I don't think, so do you?

Max Chopovsky: 45:49

Nobody's ever asked me that before. I think that every story has a moral, even if it's not explicit.

Delia Cohen: 45:59

Okay.

Max Chopovsky: 46:00

There could be a story that's just told for entertainment purposes, but I still think that if you really think about that story, you'll find a moral in there. What do you?

Delia Cohen: 46:09

think Maybe you're right, I don't know. What I think is compelling about the prison stories is that prison, in its nature and its very nature, is isolating and hiding. It's removing people from society. So I think that's where this fascination in America for true crime stories and anything about prison stems from, because it's an unknown world that most people don't get a glimpse of. So I think that the stories from prison are so popular because it's a glimpse into a world that they can't see, that's hidden from them purposefully, purposefully exactly.

Max Chopovsky: 46:56

Well, last question If you could say one thing to your 20-year-old self, any one thing, what?

Delia Cohen: 47:05

would it be? Just keep going, keep experiencing. Life's never going to be boring. I don't know. I've done so many different things in my life so I don't know if I have anything of great value to import, but I like the way that I've tried many, many different things, and I mean the hardest thing that I ever did was leaving the country and traveling around the world on a $1,000 around the world ticket for three years, way before there was email or cell phones or an American's. The economy wasn't even globalized back then. But so just keep going.

Max Chopovsky: 47:49

Actually, that is highly underrated advice, because when people are younger there's a lot more uncertainty and for many people there is a lot more sensitivity to that uncertainty. And so simple advice just keep going. I have a lot of people give that same answer because it's valid.

Delia Cohen: 48:10

Okay, good yeah.

Max Chopovsky: 48:12

Not that you need the validation from me, but it is a great answer. Well, that does it. Julia Cohen, criminal justice activist, organizer and architect of Platforms for Change. Thank you for being on the show.

Delia Cohen: 48:28

Thank you for having me, Max.

Max Chopovsky: 48:30

For show notes and more head over to MossPodorg. I find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, wherever you get your podcast on. This was more love the story. Thank you for listening. Talk to you next time. Bye.