50: Peter Himmelman

Source: Peter Himmelman

“He grabs the gunwale and starts rocking our canoe back and forth.”

About Peter

Peter Himmelman is a Grammy and Emmy-nominated artist whose incredible career spans not just decades but disciplines… a wild rollercoaster of a life for a contrarian polymath.

For some people, music is a passion they discover later in life, perhaps stumbling into it serendipitously, almost as if their fate could have taken another turn at the crossroads. But Peter was predestined for the staff and clef.

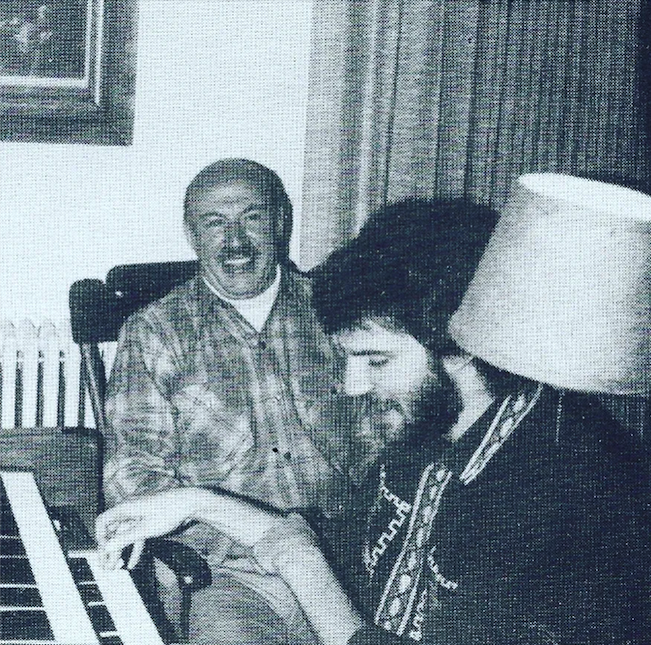

Born in the St. Louis Park suburb of Minneapolis, Peter grew up in a house filled with music. His dad owned an 8-track music store and would bring home Hendrix and Joplin, his mom enjoyed Ahmad Jamal and Thelonious Monk, and his uncle introduced him to John Lee Hooker’s Endless Boogie, a track Peter played time and again. His older siblings, meanwhile, played tracks like The Animals’ House of the Rising Sun, which hypnotized Peter and connected with him on a deeply visceral level.

And so, at 12, Peter embarked on the rock n’ roll journey, getting his first guitar, a Fender Duo Sonic. He convinced a group of high school friends to skip college and instead focus on their band, Sussman Lawrence, in which Peter was the lead vocalist and guitarist with a stage presence both magnetic and undeniable.

In 1985, Peter pursued a solo career, scoring a record deal and moving to LA, where his music videos were in regular rotation on MTV, and he continued his ascent with releases such as From Strength to Strength. He would go on to release 24 studio albums, including five award-winning children’s albums, and nearly 20 greatest hits compilations, live albums, and rarities releases.

However, having lost his dad at a young age and his sister to a car accident, he knew that fame was not the end goal. His priorities centered around what mattered – family and faith – and utilizing every second. This would require limiting his tour schedule and focusing on other projects, which he pursued with his usual enthusiasm.

So then, why a polymath?

Well, among other projects, Peter has scored shows like Bones, Judging Amy and ER, and nearly two dozen movies. He is a bestselling author, a professional speaker with a captivating TEDx talk, a visual artist, streaming pioneer (his show Furious World started in March 2008), Ivy League lecturer, and the CEO and Chief Dream Enabler of Big Muse, a consultancy that helps organizations unlock their teams’ latent creative talent.

Ironically, as someone who may not have sought the limelight, Peter has been rightfully recognized for his contributions, winning over a dozen awards in addition to his Emmy and Grammy nominations, and being featured as the subject of the documentary Rock God.

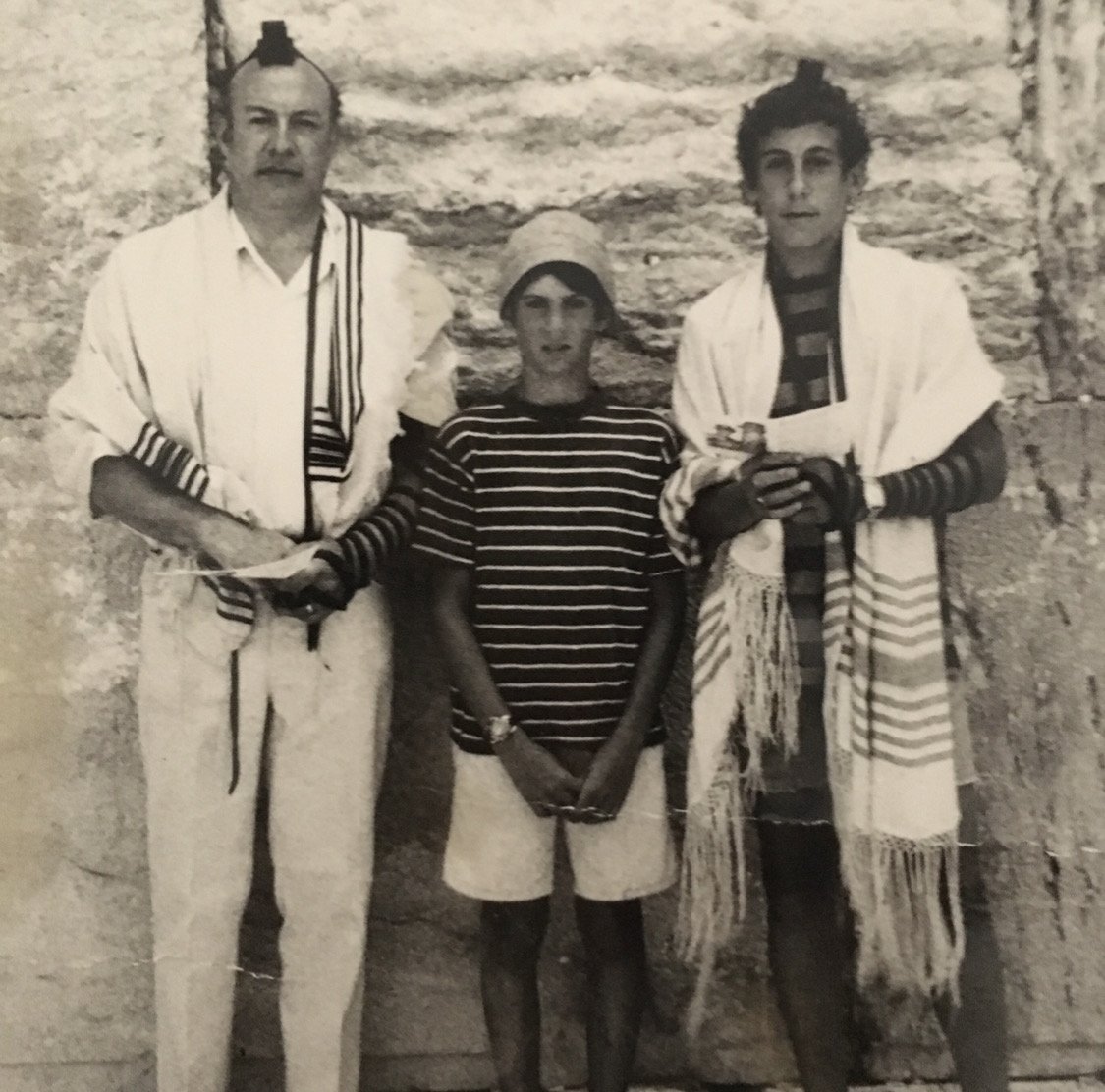

A man of principle, Peter is an observant Jew who once turned down the Tonight Show because the taping would conflict with the Jewish holiday Sukkot. Perhaps he inherited this trait from his grandmother, Mrs. Mildren (Min) Himmelman, a beloved community member and activist who was the first Jewish woman to run for the St. Louis Park… City Council. Or, perhaps, it was his father David, the “Jewish Marine” who loomed large in Peter’s life story and whose untimely passing pushed Peter to rebuild his own family.

And rebuild he did. Married for over three decades, Peter and wife Maria were connected by her father, Bob Dylan – as good a matchmaker as he is a songwriter – and their hearts are full with their children and grandchildren, one of whom graced Peter’s album Press On.

Books

-

Max Chopovsky: 0:02

This is Moral of the Story Interesting people telling their favorite short stories and then breaking them down to understand what makes them so good. I'm your host, max Jepowsky. Today's guest is Peter Hamelman, a Grammy and Emmy nominated artist whose incredible career spans not just decades but disciplines. A wild roller coaster of a life for a contrarian polymath. For some people, music is a passion they discover later in life, perhaps stumbling into it, or it's serendipitously, almost as if their fate could have taken another turn at the crossroads. But Peter was predestined for the staff and clef. Born in the St Louis Park suburb of Minneapolis, peter grew up in the house filled with music. His dad owned an eight-track music store and would bring home Hendricks and Joplin. His mom enjoyed Amma, jamal and Thelonious Monk, and his uncle introduced him to John Lee Hooker's Endless Boogie, a track Peter played time and again. His older siblings, meanwhile, played tracks like the Animals' House of the Rising Sun, which hypnotized Peter and connected with him on a deeply visceral level. And so, at 12, peter embarked on the rock and roll journey, getting his first guitar, a Fender Duo, sonic. He convinced the group of high school friends to skip college and instead focus on their band Sussman Lawrence, in which Peter was the lead vocalist and guitarist, with a stage presence both magnetic and undeniable. In 1985, peter pursued a solo career, scoring a record deal and moving to LA, where his music videos were in regular rotation on MTV, and he continued his ascent with releases such as From Strength to Strength. He would go on to release 24 studio albums, including five award-winning children's albums, and nearly 20 greatest hits compilations, live albums and rarities releases. So why did I call him a contrarian? Because all of these accomplishments, which would fill another person's lifetime, are only a part of his story. You see, he may not have had the dizzying rise to superstardom like his father-in-law, bob Dylan, but this was on purpose. Losing his dad at a young age and losing his sister to a car accident, he knew that fame was not the end goal. His priorities centered around what mattered family and faith, and utilizing every second. This would require limiting his tour schedule and focusing on other projects, which he pursued with his usual enthusiasm. So then, why a polymath? Well, among other projects, peter has scored shows like Bones, judging Amy and ER in nearly two dozen movies. He's a best-selling author, a professional speaker with a captivating TEDxTalk, a visual artist, streaming pioneer to show Furious World started in March 2008,. Ivy League lecturer and the CEO and chief dream enabler of Big News, a consultancy that helps organizations unlock their team's latent creative talent. Ironically, as someone who may not have sought the limelight, peter has been rightfully recognized for his contributions, winning over a dozen awards, in addition to his Emmy and Grammy nominations, and being featured as the subject of documentary Rock God A man of principle. Peter's an observant Jew, who once turned down the Tonight Show because the taping would conflict with the Jewish holiday, sukkot. Perhaps he inherited this trait from his grandmother, mrs Mildren men himelmen, a beloved community member and activist who was the first Jewish woman to run for the St Louis Park City Council. Or perhaps it was his father, david, the Jewish Marine, who loomed large in Peter's life story and whose untimely passing pushed Peter to rebuild his own family and rebuilt he did. Married for over three decades, peter and wife Maria were connected by her father, bob Dillon, as good a matchmaker as he is a songwriter, apparently, and their hearts are full with their children and grandchildren, one of whom graced Peter's album Press On. So, like I said, a wild roller coaster of a life, and especially germane analogy, as Peter knows that he doesn't always have control of where his life will take him, but he will be present with every moment, the ups and the downs, and it may not be easy at times, but, in his own words, nothing that matters should ever be easy, should it, peter? Welcome to the show.

Peter Himmelman: 4:11

Thanks, Max. What a beautiful writer you are. First of all, You're burnishing these little credentials and making them shine in a way that my mom would be ecstatic about.

Max Chopovsky: 4:22

I don't have to do anything to make them shine, my friend. They shine with a light all their own. I'm just a documentarian, so you are here to tell us a story Before we begin. Is there anything that we should know? Do you want to set the stage?

Peter Himmelman: 4:43

This is a little moment in my life. It's funny to give a little context to these kind of stories. In general, the idea that we have perhaps trillions upon trillions of tiny moments in our lives and so very few of them are implanted indelibly in our memory I'm always interested in what is it about a certain story that makes it really stick? Why did that particular story, that place and time, what about it created this, as I call it, an indelible memory? So my dad, whom you just spoken about, was indeed a really heroic figure in my life. Some people that never met him would say that I idealize him after he had died. But because there's so many other people that were not related to him that say the same thing and totally agree with this idea that he was a singular person for whom anyone that was near him felt empowered, that's a sort of a rare thing. There's maybe three general categories of people. The main one, which probably includes 99% of people, is it just come and go and maybe they talk about the weather. They don't leave a lasting impact on us, they're just part of the scenery. And then there are those who are really 0.5, just dreadful, like viruses, and once you make contact with them, for reasons either explicit or unknown, they just leave you feeling horrible, just like shit, like disempowered. And then there are people like my dad, who are similarly few in number 0.5 out of my 99.9, if my math is right who, for some sort of inexplicable reasons not that there's some wise words that were said that no one else could say, but by the very power of their presence can make people feel that the doors of their aspirations, which may have been closed for various reasons, are now swung wide open, at least for the time being. And I was fortunate enough, by no dint of anything that I did, and it was purely providential in my mind, with a capital P, that I was born to this man. And I feel people talk about the 1%, or people that had somebody that's born, a certain hue or something or had a certain amount of money, those things that make life so much easier for them. And this is that in the extreme, that I never had anything from him that wasn't empowering. He would get mad at me and one time I was playing the piano, sort of when I was a kid, and I was making too much noise for my mom and I was trying to like play something great, and she said to me would you stop that racket from the kitchen? Or something like that, something that anyone would say, and because my ego is so huge, I sat under my breath fuck you. You know I was probably 12. Well, no one swore in our house and when my dad had that information relayed to him, he smashed me up against the wall how dare you say that to my woman? And while I was being like thrown against the wall even as I was being thrown against the wall, not like super hard, but like hard enough to notice I felt that was a just thing that he was doing, because don't be dissing my woman for anything. I love that and I feel the same way about my wife. Just, you know. So when I was 12, it was before my Burmitzvah and my dad had a sort of a closer relationship in some ways with my older brother. They had a lot in common. My brother started working for him as a mechanic. My dad was a serial entrepreneur. He started a car battery company that he thought could was called Rexon. He thought it could go up against Sears, die Hard. He had the first eight track tape store in the Midwest. You know eight tracks, it was the new thing. He had the first Suzuki dealership in the Midwest. Japanese motorcycles. When they were like what, what is that? They used to call them no offense to anybody rice burners. You know horrible ethnic slur. And he heard about this thing called cross country skis and he started the cross country ski chalet. At one point the eight tracks, the Suzuki's and the cross country skis were all sold out of one small store. So you know, he just had ideas that he was bravely and my mom was bravely able to allow him to do this, to manifest. So when he and I would be together it was sort of a nice outing, a rare thing. My dad was also an eagle scout. He was a Jew that when I remember somebody had said some racial slur, you fucking Jew, or something, my dad took that guy and laid him fucking out. It wasn't a question of don't say that again. My brother and I talk about that like dad never said try that again If something needed to be dealt with. There was no second chance. He did the same thing with some guy that was abusing physically some woman and that got him nuts. So we had a special outing. It was the Eagle Scout and we decided we would go canoeing on Cedar Lake. Minneapolis has many lakes, city lakes, and they're all pretty lovely, but Cedar Lake had a special quality. It had this beach that there were beaches for very wealthy homes and there was one beach strewn with gravel and weeds and it was. We called it. You know, the Indian beach, the Lakota Sioux, you know were. You know that's who we stole our land from, basically, and they were fearsome. My cousin, jeff Victor, had his swin stolen. He was thrown into icy water. Another guy, mendel Meltzer, was punched in the face by these people. So it was terrifying. They're terrifying people. You know the story went setting that up. So we're canoeing Cedar Lake. My dad is in the stern, you know, providing the steering and everything. He was a great canoeist. I wasn't a middling canoeist Still am. I was in the bow, you know, trying to create some momentum and we kind of. It was a beautiful like autumn, you know, early autumn day, and the trees were just starting to turn and we're just paddling around and I don't remember what we spoke about, you know like. Pete, you know how's that guitar of yours it's really nice. He used to come in down in the basement and hear me play and I'd turn on the reverb and he said why don't you set it all the settings to five? Like he knew nothing about rock, but he was really into it, you know. And I said, hey, listen to this, dad, I'm putting the reverb on, it's like I'm in concert. He was just sit there and laugh and he goes. He said to my mom I don't know where he comes from, bevy, you know, I basically came straight from him, even though he was a terrible musician, I think it was tone deaf, literally. But as we're canoeing you could hear across the water some sort of noisy Bakhanal taking place. The water carried the sounds and I realized this must be a gathering of these Native American people that I feared so much and I knew my dad was not going to do anything dangerous. So obviously we would steer clear of that area, of that gravel strewn Indian beach, as it were. But my dad, you know, was in bit back and we were getting closer to that beach and it was uncomfortable for me, but my dad, you know, I trusted that he wouldn't go there. We got closer and closer and I could see them on the shore now and it looked as though we were heading straight for them. There was one sort of muscular, shirtless man on the shore among the crowd of, say, 20 or 30 revelers. They're all men, native American men and this shirtless man dives into the water and he starts swimming and swimming quickly. Well good, swimmer towards our canoe. Now I'm like really afraid. And he's getting closer and I don't want to turn around because if I see my dad afraid I will be shitting a brick in that canoe. My dad is smiling, laughing. The muscular shirtless man comes to the canoe we're still in motion. He grabs the gun, whale on the side of the canoe and starts shaking the canoe, rocking it back and forth. Now I'm just like what? And I'm looking at my dad and he's laughing and he takes the paddle and he waxed the guy on his upper back, not like super hard, like he's trying to hurt him too bad, but definitely hard enough to make it known that this is not a man to fuck with. The guy lets go of the canoe and kind of swims away. Now, from what I know of many cultures, the Jewish culture isn't like this, but many cultures. The Caribbean culture is like this Because I've played in Caribbean bands in my day when I was a kid and they would go down a road and they would play the kaiso. I had to throw that little accent in there. There are cultures for whom manliness is a real like stereotypical manliness is a real important thing. Now, for those revelers on the beach to have seen one of their own get demoralized and have to retreat was the most hilarious thing they'd ever seen. And they were laughing their asses off. And they were laughing like you got just pummeled by two white men in one of our fabrication of our own native watercraft. It just was like, and I was like we got to get the fuck out of here right now. And my dad paddles into the shore, right into the midst of them. They help drag the canoe up on the beach. He sits down with them. They give him, offer him, because he never drank, you know, some of the ripple wine, that, that the Mogan David wine that they had been drinking. He refused, but they sat with him and he started talking to him about, you know, adult shit like taxes and subsidies and government stuff that they were interested in and they gathered around my dad. It was so comfortable that I became bored and I started making like a little fort, like a little dam with sticks trying to like trap minnows by the edge of the water. When it was time to go, my dad got off, dusted off his pants you know, his trousers. He never wore jeans, god forbid and they gently and peaceably and graciously pushed our canoe back into the water and my dad didn't say a damn thing. We paddled. You could hear the sound of the trains running to the north of us. You could hear the sound of the looms. The sun was beginning to set and we paddled back. And I just was thinking my dad, he's a master at something that I couldn't then describe. He was a bridge builder, he was fearless and he had incredible love for people and it taught me that in most situations, not all an extension of humanity and love can bring out that love and humanity in another person. He was the most instructive day I've ever had in my life.

Max Chopovsky: 19:01

That's incredible. That is incredible. I had no idea where you were going with that story and I love, I love its undulations. It's fantastic. So did you ever talk to your dad about the way he experienced that day, or at least that canoe trip?

Peter Himmelman: 19:24

No, no, I didn't you know sort of the deepest conversation that I ever had with him. I mean. In other words, we were so close he didn't say like I say to my kids, I love you. I don't know that my dad ever said those words, but there was no need to have said that. I mean, it wasn't, it was axiomatic. But when he was in the hospital he had lymphoma. He was diagnosed with stage four when I was 17. And it was kind of an upending of one chapter of my life, the chapter of things that were just pretty normal and pretty nice. But I remember him saying to me he was one of the few people that called me Pete. I liked that. Not very few people do. And he said you know, pete, he was probably 53 at the time. And he said, you know, I just I feel like I haven't accomplished anything with my life. And you know he had all these dreams about one of his companies was called Silent Night. He made up the name, you know, silent, with a K Night. He was very clever with those things. And he made a low cost security system. The first version, iteration one, was just a camera with a fake red light that you'd use for low cost. You know deterrence. And then it became more sophisticated and he sold it to Honeywell. And he sold it so early. I mean we were not poor but we were certainly not even close to any kind of wealth. And you know, I never did anything with my life and I said, dad, you raised a family in which every single member of that family loves one another. No one is trying to hurt or disable or seek the besmirching of one to gain the attention of another, or something. That's a remarkable achievement that most people will never attain at any level of money or fame, god knows. That's like antithetical in so many ways to these kinds of things. I don't know if that was moving to my dad, but that was the truth. I mean that was the highest achievement. And I see now you know I'm 64. So I see how rare that is in any family. He and my mom I mean I don't mean to leave my mom out of this, she was completely a partner in all this. I only think about my dad, maybe because he died so young.

Max Chopovsky: 22:21

Isn't it strange tragic is another appropriate word that the benchmarks by which people judge themselves are sometimes so wrong, so inappropriate, and they fall so short of their actual accomplishments, like they don't give themselves credit for these things. You know, we look like, how we identify ourselves as people. What are the most important parts of our identities as we see them are, for a lot of people, things like professional accomplishments. For a lot of entertainers, it's fame and money, and now it's followers on Spotify or social media or whatever. And if you ever think about the perspectives of the other people in those people's families, if they're fortunate enough to have a family, none of those people care about those things. As I think about it, my kids don't care what kind of car I drive, they don't care what kind of house we live in. They don't care how much money we make, you know, past a certain point. They care that I am there with them, spending time with them, and they care that I'm present. And so I think about my life and the different perspectives that are useful to have on my life. What I mean by that is there's my perspective of what I've accomplished in my life, but then there's my kids perspective of what I was like as a father when they were young. As they get older, my wife's perspective of me as sort of the member of the family and I feel like a lot of the time, the standards by which we judge ourselves are not only inappropriate but they're not important to the other people in our life. It's just that's why use tragic as a word, because your dad said I feel like I haven't done anything in my life. And you said you probably thought to yourself I don't know if you said this to him out loud, but, dad, you're looking at it all wrong. I understand that this is real to you, that to you this feels like a shortcoming, but to me you've taught me so many lessons that you might not even have realized. You taught me, like that day on the canoe that you never talked about after we came back, but it was one of the most useful lessons I ever learned in my life. I wonder if you ever spoke to him about that.

Peter Himmelman: 25:09

I think one of the reasons I like to write songs is because the song acts as kind of a duck blind behind which I can hide and say anything I want. So you know my dad. His prognosis was like I don't know what, like a year, and he lived for four years and at the end I had been playing in my band. I was 23 years old, or 22 at the time, and we were playing some of my greatest hits. I'm your fireman, show me where you're burning. I'll be there to hose you down. I'm your, torture me all night long, love me tough, love me strong. These are different songs. Torture me and fireman this is one of our hits cigarette, baby, let me be your cigarette. Puffa, puffa, puffa till my tip gets wet. Light me up and, baby, don't fret because, girl, I wanna be your cigarette. I mean, these were funny, crazy songs that you would definitely get canceled for now. But I was also writing other songs which were kind of the precursor to what I'm doing now. So on one of these occasions, while my dad was like at the end it was the night before Father's Day, it was Saturday night we were playing at some like the country dam, at some place in Wisconsin and I was living at home in the basement when we weren't on the road and I got home after playing cigarette and torture me and there was gonna be a party for my dad, my mom had said you need to cheer him up, write a funny song for dad. I can make a funny song pretty easily and I got home and shit, they didn't write a funny song. I think by tie or cologne or whatever you're supposed to buy on Father's Day, the refrigerator's full of like locks and bagels because the cousins would soon be coming. It's like it's four or five in the morning now and I'm sure you've had these moments as a writer. I know you have where you're, just things just come to you and you just hold a basket and there they fall. And that happens to me, it's happened many times and I started picking on this finger, picking on this nylon string guitar and sort of. I was in the basement. I could see through the window well, that the sun was starting to come up and the cords. You know that I was playing and I was just tired. I was still in my stage clothes, it was. They had just sweat, had dried on the way home on the to our ride and I start writing and I realize I'm writing a song about my dad. And I finished the song and I had this four track cassette board of studio which I recorded all my demos on and I wanted to record the song because I wanted to play it at the party. Kind of a strange way of me to just cut through the shit and I record the song and at the end I start to cry. And there's me crying at 22 or 23 at the end of the song and I I debate for a second Should I record it over like a better tier free version? And I said, fuck it, I'm leaving it. The cousins now come. It's 10 o'clock, the locks and the bagels and the Tropicana orange juice, everything's out. And I come upstairs and my mom's like did you write a song for dad? I'm like I did and I throw the cassette on and so strange. It must have been my mood or my eyes or something like that. But as soon as the tape hiss came on before the song, people started to cry. Everyone left the room when the song came out because no one wanted to say this is happening. It was just my father and me listening. And then we held each other and cried. We held each other and cried while the song played, and he carried the cassette with him in his Muntzingwear shirt in the pocket for a month until he died and they played that song at his funeral. So then I moved to New York after he died because that was our plan and we're still trying to get baby. Let me be your cigarette and all those songs that were playing at Warner Brothers. People were debating whether to sign us or not and they didn't, and I was like sort of bummed that they didn't know. I'm in retrospect, god. Thank God they didn't. I'm still at the play. That shit, my kids would hate me. They probably wouldn't even have been born because my wife wouldn't have married me. But I got a call around this time while we were living in the band house like the monkeys in Ridgewood, new Jersey, where all the band had moved because we couldn't afford New York. And this woman's name is Ruth Grosh and she had been a woman who paid me several, several thousand dollars when I was like 18 to compose music for a teddy bear called Spinoza Bear with these uplifting themes that was later used in like crisis centers. There was a woman whose child had never spoken, never looked at anyone and was like in a locked in syndrome, and she wrote me a letter. This is the only one I remember because there were many letters. The first time my child got up and walked and hugged something other than himself was to this bear and I wanna thank you for bringing the child out. I never thought much about this bear really, because it just was some money for me and some thing you know that could get us to New York. Well, ruth Grosh, who was the brains behind the bear, called me and said I've just been in touch with psychics this is about like eight months after my dad died and they asked me a disturbing question. I told him about you and they said does he want to remain on the planet. We feel that his life is going to be short. I'm like holy shit, I'm sitting there with a phone stretched into the living room, you know, with a cord, because before cordless phones and she said would you like to come and meet these people? It's a husband and wife. I'm like not really, but I guess. So you know, I'm gonna be in Minneapolis in a week anyway. So we met Ruth took me she had like new age music on the way to Northern suburb of Minneapolis and we meet the two psychics. And it's a husband and wife like tag team and it was just like weird. They had sort of a plush carpet in their apartment. And then we go upstairs and they sit me in this kind of faux leather chair and they're both like on either side of me and they play a little game and the game was name a person and I'll tell you about that person. So, number one I asked about this girlfriend I had, and they gave me some like pretty good information, but you know, whatever, I'm not buying it. And then my cousin, jeff Victor, who plays in a lot of my albums. He's one of my best friends, a genius, literal, using the word you know with discipline Genius musician, genius person, by the way, any genius musician is a genius person, it's goes to say, in any subject. And he has suffered from childhood with these ticks, like facial ticks and he's kind of funny about them, and in hands and there were different ticks where he'd raise his hand, like up, he couldn't control his hand from going up, stretching up, and we keep called that reckless greeter. Another one was called round the world and his eyes would spin round, round, round. Another one was Southerner, where he couldn't control his thumb from, like turning down down south that we call it Southerner. So I said to the psychics okay, jeff, not Jeff, victor, just Jeff. Now this was freaky. The man and the woman stare at each other. The first thing they say is he can't stop, stop the music it's pouring out of him at all times. The man's eyes start rolling like round the world. I'm like what in the fuck is going on? The woman's hands are going up like reckless greeter. I'm like holy shit. She says, well, ask one more name. The morning that I left for this psychic experience, my mom was at home. I was staying with her. She was the only one at home now my siblings had moved out. She was going on her first date since my dad had died. Maybe it had been a year and a half or I don't know what it was. He was the contra base player of the Minneapolis Symphony and I've never seen my mom like this. She was flitting around the house like nervous, like a school girl, and trying on outfits. It was just. It was very off putting, but I understood that my mom needed to get back to life. She'd suffered so grievously and it was. I'd never seen anything like this. And I said to the psychics Beverly, they start giggling Whenever adults giggle. It's strange. But when they're giggling in concert with one another about the name of my mother, which they don't know who it is, it's really weird. The woman says she's excited about something, but she's also very nervous about whether it's right. The man giggles and said she's acting like and I quote, a school girl. I'm like, okay, the jig is up, I'm over, okay. So then they get into it. How do they broach the subject? Am I out, me dying? The man says is it your wish to leave the planet? And I think about it, because I'm now aware that I'm so lost, so dizzyingly depressed, that maybe not really, but it needs to be considered. And I wait a little longer than one might. And I say it is not my wish, I don't wish to leave the planet. And the woman says we both feel that by playing pop songs to get a record deal, you are denying something of your essence and in so doing you are shortening your own life. You love the blues, you love reggae, you love meaningful things and all of a sudden, like a train in the dark, like the rrrrk, I'd never thought about that song that I'd written for my dad. It was in a closet, on a cassette somewhere. I never did anything, it was meaningless to me, it was just a memory. It wasn't a song that anyone would wanna hear on the radio or something. I said there's this song that I wrote for my dad and it said very apropos, long-windedly, of your question. It said everything I ever wanted to say to my dad and he heard it. And they said I think you should put that out as a single. And I said I'm putting it out as an album around other songs of meaning. And that album got me my first record deal on Island Records.

Max Chopovsky: 38:31

Have you ever read? Have you read Just Kids by Patty Smith?

Peter Himmelman: 38:36

Sure yeah, I have.

Max Chopovsky: 38:39

What I find so interesting about that book is it all seems to make sense if you look at it in hindsight. Well, of course they were in this place at this time and they were at the Chelsea where everybody hung out, and of course they increased their chances of running into the right people. But as it was happening, she and Robert had no idea that any of that was going to happen. Looking forward, it's like Steve Jobs said in his 2005 Stanford commencement speech you can only connect the dots looking backward. But that's of little encouragement to the person who's looking forward and has all these dots that are flying around that they have no idea how to connect. And I just started reading this book called 4000 Weeks by this guy named Oliver Bergman, and the title of the book is sounds like a self-help book because it's something like time management for mortals or something like that. But what he talks about is we want to harness time in a way to squeeze every possible bit of efficiency out of every second of every day, and that is not only futile but counterproductive, because what we have to do is to accept the fact that we'll never please everybody, we'll never get everything done, we'll never get to inbox zero, we'll never get an A in every class. And once you accept that fact that there are some inalienable truths that are contrary to the stories that you've been telling yourself it'll actually take a massive weight off your shoulders, because then you'll just be able to live your life without trying to control every single day. And I think that it sounds like that's what you learned relatively early on in life that actually a song that you might have written that was just meant to be a conversation with your dad, and then you put it away, right, because it had served its purpose, or so you thought. That was the song that finally got you to a place, to a milestone that other music that you had been writing could not get you, because you went with the flow. And I think there's also something to be said about the fact that that song probably came from a really, really personal space and, as you said, it just started coming out of you and you just held out the basket for all the fruits to start falling into it, right? It's like Rick Rubin says as artists we are just receptacles for the source and when it comes at us, you just have to receive and keep receiving until it stops, because it will stop. And so what you did there is, as I can tell, is leaned into that unpredictability, gave up the control and said, well, maybe this is the song, maybe this is the song that I want other people to see the light of, to hear it, you know, for it to see the light of day.

Peter Himmelman: 42:19

I'm going to go back if I made it something you're talking about where the families didn't receive that kind of love, or we de-prioritize the things that we in some some days of the year or special holidays that we do realize those are the priorities family love, togetherness. The way that I see it and you know this is talking a little bit about my Jewish practice of, you know, 37 years the way that I look at things, and I looked at these things, by the way, when, this way, when I was a child, not in any sophisticated terminology that's why my sort of return to Judaism not that I ever converted out of it, but you know to think about it as a relevant source. That's why it was so easy for me, because it was so familiar. And one of the things that was familiar is that I sensed a duality within me, and I'm going to give it terms that maybe sound anachronistic to some of your listeners, and you know the ones who are very sophisticated. I never went to college, by the way, so my, I never got tainted by anything too badly. But there's a duality. Call it I won't use words spirit, but call it essence. There's essence which is undefinable, it's eternal, and that essence is sort of our consciousness or our cognition. Some people just relegate it to some sort of electromagnetic frequencies in the brain and they all disappear when we die. I granted that's one probability. It's not one that I think is as probable as that there is a creator with a capital C that's making everything happen at this time. That's just a thing that makes more sense to me. But the duality is one is of essence, of meaning, and one is our physical bodies. And why is it that we prioritize things? And I do the same thing. I'm not like some sort of person who has grown out of this, I'm struggling with it all the time. I'm generally a total asshole. But why do we as human beings gravitate so easily to those things Like we want this acknowledgement, we want this, whatever it is that we want on a physical level? Because we're physical beings. And if we don't pay some attention to this essence of ourselves and when I mean pay attention, I mean pay attention like a classical pianist plays attention to piano every single day and practice for hours a day making that attention to essence become a regular, prioritized part of one's day, that sense of essence will fade away. The forces of entropy which act upon everything, will certainly act upon that as well, at least as it's manifested in our lives, and then we will be left not with a 50-50 ratio of essence to meet sack, let's say temporal, corporeal being. We will have 99 meat pack and maybe just a flicker of essence. And one of the jobs that I see humanity needs to take and for sure I'm part of it and, like I said, I'm an asshole most of the time needs to work on is identifying that essence, which isn't like yoga, by the way, or something that's going to make me a more flexible person. It's not about personhood here. It's not about selfishness, it's not about self like self-magazine. That was when you knew society was going off the rails. I want to strengthen myself in that essential part of me, not only for myself and not only for my family, which is a huge priority, but for anyone that I encounter in the world. It isn't about I'm going to do this therapy for me. I just want to have some me time. There's too much fucking me time, I got to tell you, and that is why you see this disparity, with people prioritizing the meat sack over the essence.

Max Chopovsky: 47:03

It's so funny you say that because in this book, 4000 weeks, this guy, the author Oliver, he talks about your tendency to control everything, including your schedule means that you're putting yourself ahead of others. And there's something to be said about giving up certain loss of control by being a member of a community, because then you have to adjust to other people and their needs and their desires and their schedules. And I was just thinking actually this morning about there's this quote about I can't remember the exact quote, but it's something about if you go by yourself, you'll go farther. If you go with other people I can't remember the exact quote, but it basically implies that you're better off with other people. You might not go as far but you'll have a better experience. And I think that's dead on.

Peter Himmelman: 47:56

What is going farther mean? I'm not saying and I know it's a metaphor but what does it mean to go far? What exactly happens? You know, let's say that I drive a car to Cleveland. Well, you know, now I can fly, which is great. Now I can fly first class, which is like really great and they give you like a better kind of water or something in a glass. Now I want to fly private and I feel really special and I feel like I'm at something. But damn it, after the third time I'm flying private, I keep looking at my watch and when the fuck are we going to get to Cleveland? I'm back the same way. In other words, these quantitative measurements, including going farther in quotes, they don't get us anywhere. I mean up into a point. I mean, if you're not able to put food on your table and you know there is that point poverty sucks.

Max Chopovsky: 49:05

Let me change a letter going further with the you not farther.

Peter Himmelman: 49:10

I like that, and that implies something to do with depth as well. And I wasn't contradicting what you said in terms of just bringing a point about the race. And how do I know this race sucks and everything Like? I do it all the time. I haven't graduated it, graduated from it. Even today I'm like got to get this done. Blah, blah, blah. I asked myself why do I do all this stuff? And I finally had a good answer my cousin whom I mentioned, jeff Victor, with the Southerner. He said to my wife you know well, peters does all this stuff. He doesn't really care what people think, he just does it, which is totally untrue. I'm just unmoored if somebody doesn't like what I do. And I said that he goes. Well, why do you keep doing it? And I had to think about it. The only reason I keep doing it is just feels good. It's one of the things I do in life, like painting or whatever it is that just makes me happy. And if I'm happier, I'm better able to get in touch with this essence.

Max Chopovsky: 50:22

Honestly, sometimes it's that simple. I think people just they just overcomplicate it. And there's no need to complicate it, because the essence of a lot of things is simplicity, right. It's simplifying to still things down to their essence. The truth crystallizes, right. So, like when I was backpacking through Europe, I went backpacking a couple of times. One time I was by myself. I happened to have a few weeks between one job and my other job, which was my first job in Chicago, and I wanted to go backpacking in Europe and I couldn't find anybody to go with me. So I just went by myself and I just remember thinking, man, it's great that I didn't have anybody else's schedule to think about or what anybody else wanted to do, and just I could make my own plans and do whatever I wanted to do, and I would meet people along the way and it would be great. And I did do a lot. I saw a lot of things, I met a lot of people. But now, as I think back on that I realized and this is what I mean by going further with a you I realized that I might not have seen as many places had I gone with somebody else. I might not have stayed in as many cities or visited as many landmarks, but I would have had somebody else that would have shared this experience with me, and I would trade that for the solo journey. Not that there's not a time for solitude I certainly enjoy my fair share of solitude but to me it's a matter of I would rather see less, but see it with others that we could then have a shared experience together, and it's an interesting evolution of my perspective. It's beautiful.

Peter Himmelman: 52:13

I mean it's perfectly clear.

Max Chopovsky: 52:17

I think that only happens with age.

Peter Himmelman: 52:20

I was lying in bed last night you know my wife always falls asleep before I do and I'm thinking about just again, essence, the simplicity and things that we take for granted also goes into the meat pack zone and I'm thinking to myself how nice it is to have somebody in my bed every night that I trust with my life and everything in it that I love more than anyone in the world just next to me. You know I didn't tell her that, but I mean, it's just, it's so simple. Somebody said to me the other day it's like at school, and he goes you know, I used to be a mashgiyach in a lemon oil factory. A mashgiyach is somebody that checks to see that everything's kosher. Somebody didn't bring, like you know, pork in there and he said you know, I got lemon oil on my hand. Now the lemon oil that you get in the bottle that you buy is not real lemon oil, it's somehow diluted. He goes. The lemon oil, which is the essence of the lemon, was so strong that on my fingertip I smell lemon for a month. And he was sort of saying you know this? This idea of this distillation of self, of it appears even in nature. There is something immutable about one's essence, something so incredibly powerful. And it's shrouded, it's got blankets on it, even in the most sort of essence related people. And I'm just thinking now for a second. If for some reason we were courageous enough because it's only our courage that's lack or therefore that prevents us from having the essence shine. There's another Jewish idea which is interesting Panim and panemius. Those are two related words. Panem is the word for face, panemius is the essence. The goal of a person is to make their face, meaning their outward appearance, exactly as their essence is. Kill the filter. Kill the filter hashtag. Kill the filter. Kill the filter Kill the filter fish.

Max Chopovsky: 55:06

Well, one comment on what you were talking about with your wife. People say, now, my partner right, which I guess I understand why they do that. But it's always sounded strange to me like, oh, my partner and I are going to do this like, well, your husband, your wife, like, who are we talking about? But now I'm actually starting to lean into that term and ascribe a deeper meaning to it, which is they really are your partner right, like they are your partner in the truest sense of the word, that you travel this journey with them, and in those travels your bond becomes deeper and the partnership really sort of evolves and matures. So it's funny how you can glean, you know, little nuggets of wisdom from daily life which obviously you as an artist have gotten good at, because you know, I feel like that's what good artists are. They're people that see everything that everybody else sees, but they see deeper into it, understand its essence and then, through their own filter, put that essence back out into the world. And that's why people, when they hear a song that has really poignant lyrics, are like, oh my God, this person really gets me, you know, like this. I've just found that really fascinating. My grandfather was a poet and a journalist and he was the artistic nucleus of our family and as a Jewish journalist it was very difficult for him to actually become successful because he was a Jew. But he did. And when we moved to America in 1992, in 1993, the paper that he was working at was offered to him to be the editor of that paper and he turned it down because they wanted to come join us in America. But he's written dozens of books of poetry and prose in addition to his journalistic work, and what I've always found is that the poignants with which he's able to, the skill with which he's able to harness the Russian language, which is hard enough as it is, but then to use that tool to achieve such poignants where, if you read his poetry and just think to yourself, damn, I'm not alone, somebody else feels this, and the way that he said this just speaks to me in an incredible way. And my grandfather? We lost him to cancer as well because, as a crazy story, when Chernobyl exploded in 1986 and we were evacuated from Kiev, he, being a reporter, was sent to the reactor. He flew over it, for this was 48 hours after it exploded and he was sent there to document it, and he was exposed to unhealthy doses of radiation and he wrote this whole effectively expose that ended up turning into this book called Chernobyl Bitter Grass. He wrote in Ukrainian and most of it was redacted by the government because obviously nobody wanted the public to know of the colossal failures that precipitated the disaster. He was the same way, in that he was able to sort of model this ideal behavior for our family without being pedantic or prescriptive about it. He was just the man he was and, just like your dad, he was a product of his time. Life was harder back then, and so the people that came out of that environment just had a different perspective on things. So I just think that it was interesting, because there are certain of us are lucky to have people in our families that have the right priorities and have an incredibly, just, an incredible philosophy right, and I feel like you and I have that in common. For you it was your dad. For me it was my grandfather. I just think that we're very fortunate in that respect.

Peter Himmelman: 59:17

Yeah, I mean, I can see where you got your writerly sensibilities Strictly from him. That's model behavior, that's privilege. That's the word I was looking for.

Max Chopovsky: 59:29

Really is, it really is?

Peter Himmelman: 59:31

I mean check my privilege. I'd have checked it and I fucking love it. What can I say?

Max Chopovsky: 59:38

When you have a duty to pursue it on some level, have a responsibility for I'm very cognizant of that.

Peter Himmelman: 59:44

It's not just like I feel very motivated by that idea.

Max Chopovsky: 59:50

That's exactly right. So let's go back to the canoe story for a bit. What would you say is the moral of that story?

Peter Himmelman: 1:00:02

Don't be afraid to give of yourself. Don't be afraid to show the love that you have. The rewards are incredible and unknowable for oneself and for the world.

Max Chopovsky: 1:00:20

Couldn't agree more, and the earlier the better, and you'll, most of the time, have to lead with that vulnerability, but it's worth it 10 times out of 10. Why did you choose that story?

Peter Himmelman: 1:00:33

Well, just I heard you talking about my dad in the intro. It could have been another a number of stories, but you know you set it up. Something that was meaningful to me. I mean I have a lot of stories. It's funny when you write about your own life. It's kind of easy. Some things have just happened to me. The people that I've, you know we came from a very small house, like in a suburb and the people that I've met. You know I look at the word in Hebrew, haskah aprotit. It means like divine providence, and that I do see now. In that sense, I mean, I've learned enough to know that, for example, I'm playing a show in Chicago soon and I know that my ostensible reason is to go play a show. But I also know and I know it very well I will be astute to looking out for reasons beyond the ostensible, and they always appear, and many. They appear in many myriad ways. Wherever I go, it's just like you and I are talking right now, or ostensibly, I'm doing an interview with you, something on my schedule. That's the practical side, that would be called the meat sack side, but there's something essential here. It could be. I hope it is that you and I forge a really solid friendship and that will transcend time and place and it will lead to many other things. I'm aware of that, and I'm aware of that even when I'm with you, and it doesn't stop me from doing my meat pat job. It only helps.

Max Chopovsky: 1:02:23

Well, I would absolutely love that. That would be incredible. What's interesting about life, I think, is that any of us, if we do it well, we are collectors. We're collectors of stories, we're collectors of relationships, we're collectors of memories, we're collectors of experiences, and in order to collect, we have to be able to receive and we have to be able to experience, to be in that moment, to truly, truly collect something. And I've struggled with that in the past because oftentimes, with all of the meat sack, parts of that take up so much of your bandwidth. You're thinking about what's next on the calendar, what am I making for dinner tonight? You're thinking about all these sort of banal things which, by the way, are all part of the human experience and not to discount them whatsoever but sometimes they just take up so much bandwidth that it's hard to be a collector. I suppose maybe that ties back to this whole 4,000 weeks theory, which maybe we just have to be okay with, the understanding that we won't be able to collect everything, but the things that we collect, we're going to really, really collect them.

Peter Himmelman: 1:03:41

Right and you don't even have to work on it, viscerally implanted in one's mind, you don't have to. In other words, it would be contradictory to work on your collection experience In some way. The things that happen that are collection worthy, it would seem I'm just surmising here they're so inordinately special or connective that the body and the mind goes into like a different state automatically. And I worry that if I for myself, if I had this cognizance or this desire to trap it, I would miss the sort of automation, the automatic modality, and I would go into this intellectualizing, this kind of like writing a song, if you're intellectualizing as you write, in the same way, when you're writing your prose, your beautiful prose, you reserve much of the intellectualizing for the editorial process. But even then you don't want to be completely intellectual and it would seem it could be a fearful thing for people to just let go of their intellect and allow this sort of subconscious thing to take over. This is another quick point. It's not an unfamiliar thing, it's not the provenance of artists. We dream for a quarter of our lives. We're dreaming that we're backwards on a penguin, you know nude. You know trying to whistle in Portuguese or whatever it is. You know, yeah, his name is Stan Morgenthau. He is a very, very serious man. He's an actuary. Stan Morgenthau was dreaming this hypothetical man that he'd just taken a shit at his grandmother's house at Passover. You know, on the floor, you know he's not as normal as you think he is, and to allow those things to sort of rise up, dream, let's say a creative process not at the sader is a wonderful thing, it's a necessary thing.

Max Chopovsky: 1:05:56

Well, here's what I mean by working on the collection. You do, I think, have to work on it to the extent that that work is training yourself how to be open to collecting all of these things at any given moment, because not all of them are going to be such instances of divine providence as to smack you over the head with it and be like, well, that's obviously a fucking beautiful sunset. It's like if you're in a canoe, let's say, and you're moving down the river and you put your hand in the water because you hope that some fish will brush up against it and you'll be able to tell your friends that, oh man, I felt this fish in the water as I was canoeing. But you're missing the point that, actually, what if it's just about having your hand in the water and feeling the water on your hand, and maybe that's the experience you're collecting?

Peter Himmelman: 1:06:48

Right, not the friend telling. One thing I found is very technical, very practical. Remembering is that I've written down so many stories, so many things and I've written songs about them, so they're fresh. Some of them are more fresh in my memory than my daily life. It's another weird thing. My parents and my older siblings lived in a house on Medicine Lake in Minnesota. Medicine Lake used to be kind of a woodseed place, a silvan area. Now it's just like a suburb. My dad was a deputy sheriff. He had a gun and once he a giant snapping turtle and they move fast and they can easily bite off a limb of a child was heading toward the beach really fast where the kids were playing and my dad got out his rifle and aimed and shot it under the carapace and killed the turtle before it could get into the water. And the reason I mention it is because that image and the trees and the water, it's so clear. I was never there. It's only a story, but I've embraced the story to the extent that it's become part of my memory. That's the power of a story.

Max Chopovsky: 1:08:19

Let's talk about stories for a minute. You are a storyteller and you've heard some fantastic stories as well, some memorable stories like the one you just told. What do good stories have in common?

Peter Himmelman: 1:08:31

They have unique characteristics. That is like saying absolutely nothing. You're taking me somehow both into the minutiae of the environment and of the language that was spoken, to the extent possible, of the smells and the sensory aspects. You're taking me into the world, but you're also taking me into the mind and the insights of whoever is in that story. Now, this is something a movie can't do. They try it as a cheap device to do a voiceover. The story itself, I feel, is less important than the way those two things are told.

Max Chopovsky: 1:09:21

I really like that, because those two things allow the listener to build that own world in their mind and that's how they can remember the lake and the trees, even if they weren't there to see the snapping turtle get shot.

Peter Himmelman: 1:09:35

When I was in eighth grade I was really into tropical fish. I was a budding ichtheologist. I even got it was called Tropical Fish Hobbyist and it came monthly and it was like, oh my God, herbert J Axelrod, he was like the author, he was a real ichtheologist and the tank would be glowing and I put on Radio Mystery Theater. It was such a great thing and it wasn't television, you know, because you had, as you said, you had to create the story in your head, so it was a more interactive experience. That's why people dig podcasts so much. No one imagined that pure audio would in some ways overtake audio and visual together.

Max Chopovsky: 1:10:27

Well, video killed the radio star, but then radio came back with a fucking vengeance. It did, it did. So last couple of questions what is one of your favorite books, or a couple of your favorite books, that just nails storytelling?

Peter Himmelman: 1:10:45

One of my favorite authors. Maybe you know Isaac Babel. No, he's a Russian author and he was, you know, I guess, disappeared by the Soviets for a while and after, you know, posthumously, you know, revived his work. His work is by far my favorite writing. He has a group of stories called the Red Cavalry Stories. I wish I had the right here. I usually have a copy, I have a couple copies of it, and it was the time that he was a journalist with the, you know, when the Russians were fighting the Poles, you know, just around, I think. It was like in the 1920s, and his use of language is so spare. Now it's being translated from the Russian and the translator is excellent, but the use of language is so spare and haunting and the most horrific things are described with the least amount of garish language. His quote, if I get it right, is something like nothing pierces the heart, like a well-placed period. I love that. I love that.

Max Chopovsky: 1:12:10

I love that. It's visually so striking as you imagine it, but it's also. It also makes perfect sense.

Peter Himmelman: 1:12:17

Yeah, for any writer, you get that and it's. You know, when I think of songwriting, I tell I teach songwriting. Once in a while I said you guys are writers, so it's no different than a sports journalist. Your language has to be really good. If it's colloquial language, like I ain't going down there, that's fine. But you have to know that too. You know you have to work with the language. That's. You know Wittgenstein's quote. I think it was like our world is just as large as the as our language, or something like that. It's, you know, it's a better quote than that. That's basically it. It defines the size of our world.

Max Chopovsky: 1:13:01

Totally yeah. You've got to be in support of whatever goal you're pursuing, and by goal I mean what do you want the audience to take away? What do you want them to feel? So does every story have to have a moral? And if it doesn't have a moral, is it still a good story?

Peter Himmelman: 1:13:20

I don't think every story has to have a moral or maybe another inverse way to ask that is every story in some way moralistic, without it being sort of a cautionary tale or a morality play of some sort? I'm not sure. I mean, does every story have a lesson to be taken away? I mean, it depends how creative you are. I could draw a lesson out of like anything, I suppose. So yeah, I mean, there's, in other words, there's certain things that are moralistic by nature. I don't really like those kinds of things. I don't like when a moral is spelled out too concretely. You know, I want to hear something that doesn't seem to point in the direction of morals and I want to draw that conclusion for myself, and when I do, I will feel it much more deeply.

Max Chopovsky: 1:14:20

And as the artist creating a story that may not have a moral being crammed down the throat of the audience, you are showing a higher level of respect for your audience, even though you have to give up control over the moral that's being given to them.

Peter Himmelman: 1:14:35

It's so true. I always think, like being on stage, you need to assume that the audience is super intelligent, because human beings, even ones that are, you know, we might consider oh you guys, he's pretty stupid. Their intuition, their intuitive powers are huge. They're strong, they can feel. When something lacks veracity, you know. You get up on stage. That's when you've already gotten your credibility by the way you stand on stage.

Max Chopovsky: 1:15:13

You got to let them come to their own conclusions sometimes, and that makes it so much more fulfilling for them and also it makes it more universally applicable, because everybody might come to a different conclusion.

Peter Himmelman: 1:15:26

What does it feel like to fail? It's like asking a boxer what does it feel like to be punched. Every boxer in every fight is getting punched all the time. It's not pleasant, but it's part of the gig, and if you're not doing it you're probably boring.

Max Chopovsky: 1:15:43

All right, Pete.

Peter Himmelman: 1:15:46

Yeah, I love it.

Max Chopovsky: 1:15:47

I'll let you call me, pete I say it cautiously because I'm on hallowed ground here, because I'm not a Jewish Marine. But one last question for you If you could say one thing to your 20-year-old self, what would it be?

Peter Himmelman: 1:16:04

Same thing I'd say to my 64-year-old self Be courageous, understand that you are being given gifts by God that need to be disseminated. Speak up, speak out, walk, move, have agency, be afraid, but be courageous and do it anyway.

Max Chopovsky: 1:16:30

Hell yes, hell yes. What a way to end the episode. Have agency, be courageous, be afraid and do it anyway. That does it, peter Himelman. Thank you for being on the show, man.

Peter Himmelman: 1:16:49

Max, what a pleasure, what a Machia.

Max Chopovsky: 1:16:52

It was absolutely amazing For show notes and more head over to maspodorg. Find us on Apple Podcasts, spotify, wherever you get your podcast on. This was Morrill of the Story. I'm Max Tropowski. Thank you for listening. Talk to you next time.